Ah, Friday. It’s the last day of the school week and the workweek before we can enjoy a blissful reprieve from at least a few of our responsibilities. But add a few key numbers — say, a 1 and a 3 — to this anticipated day of the week and it suddenly becomes the stuff of nightmares…at least to those of us who are superstitious.

Friday the 13th has long carried creepy connotations in Western culture, so much so that there’s even an official phobia describing a fear of the date. But have you ever wondered why? Like walking under a ladder or breaking a mirror, Friday the 13th makes many of us nervous, even if we aren’t exactly sure of the reason behind it.

While it’s easy to assume the superstition originated with (or was at least exacerbated by) the Friday the 13th movie franchise, its genesis goes back much further in time. Let’s take a trip into history to find out exactly why many people consider Friday the 13th the unluckiest date on the calendar.

The Number 13’s Bad Wrap Started Millennia Ago

It’s interesting to note that the number 13 has traditionally gotten a bad reputation in certain cultures — and has for quite some time. A myth about the origin of 13’s shady notoriety goes back to the Code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian legal document from around 1750 B.C. The Code seems to make a point of omitting the 13th law from its list of more than 200, which led some early groups to theorize that the number was associated with something nefarious. But, it was later discovered that this missing 13 was merely an early translation error — the original code wasn’t actually numbered.

Still, this potentially spawned our lasting desire to avoid the number in certain situations, just to be on the safe side. For example, the London Eye, London’s famous observation wheel, actually has 32 capsules, but they’re numbered 1 through 12 and then jump to 14 through 33 specifically to avoid a 13th capsule — or at least one that’s labeled with “13.” To this day, some hotels and buildings also jump directly from floor 12 to floor 14 for the same reason.

Some historians blame 13’s unlucky status on the simple fact that it follows the number 12, which is largely considered a perfect number. There are 12 months in a year, 12 zodiac signs, 12 days of Christmas, 12 items in a dozen and two 12-hour halves each day. Some folklorists, however, point to more religious connotations.

What Does 13 Have to Do With Religion?

Another popular theory about 13’s supposed unluckiness goes back to the Last Supper — the final meal Jesus shared with his apostles. Jesus plus those 12 disciples equals 13 guests, one of whom ultimately betrayed him. As a result, he was crucified on a Friday, which may be the first time that Friday and the number 13 combined to signify a bad omen. To this day, one common superstition claims that having 13 guests around a dinner table is an omen of impending doom or death.

Norwegian lore also tells the tale of a dinner party at Valhalla where 12 gods were enjoying a meal. Unfortunately, Loki, the trickster god of turmoil, showed up unannounced and increased the number to 13. While engaging in his infamous antics, he caused the death of Baldur, the Norse god of light and one of the 12 gods.

Some historians have also suggested that the superstition could also go back to Friday, October 13, 1307. This was the date when Philip IV of France arranged for the arrests of scores of the Knights Templar. The Knights were rounded up at dawn before being tortured and killed by the agents of King Phillip, who was intent on seizing their wealth for himself.

How Has Friday the 13th Played Out in More Recent History?

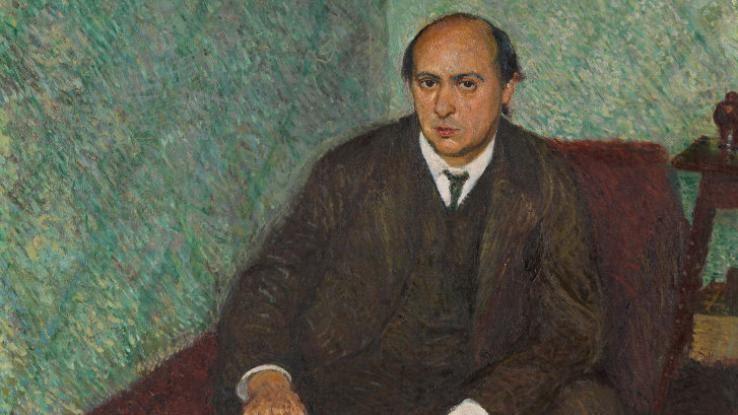

Fear of Friday the 13th isn’t limited to those living in the modern era. British journalist Henry Sutherland Edwards mentioned in his 1869 biography of Gioachino Rossini that the famed Italian composer had a healthy fear of the date. As irony would have it, Rossini ended up passing away on Friday the 13th of November in 1868.

Rossini’s fellow composer Arnold Schoenberg likewise suffered from the same fear of Friday the 13th. Throughout his life, Schoenberg developed a whole method of compliance around his fear of the number 13. He wrote the number 13 instead as “12a,” refused to enter rooms or floors that were labeled with the number and even once turned down a house he was interested in because 13 was part of its address.

As fate would have it, Schoenberg, too, died on a Friday the 13th in July of 1951. Whether these two instances were mere coincidence or examples of self-fulfilling prophecies at their finest, we may never know. But it’s clear that fearing Friday the 13th doesn’t seem to help avoid whatever evils it may bring.

Friday the 13th Takes on a Key Role in Popular Culture

Friday the 13th had been making appearances in popular culture long before most of us associated it with a murderer in a hockey mask terrorizing Camp Crystal Lake. Back in 1907, American financier Thomas Lawson released a popular novel called Friday the Thirteenth. The book told the tale of a stockbroker who took advantage of the common superstition surrounding the date to create mass panic on the stock market.

In the 19th century, the Thirteen Club consisted of a lively group of bold souls who sought to cast superstition to the wind. Their inaugural meeting was hosted in room 13 of Knickerbocker Cottage on Friday, January 13, 1882, at precisely 8:13 PM. The 13 diners present raised 13 toasts in the light of 13 candles, around a table where 13 courses were served — you get the picture.

The club’s scribe later wrote, “NOT A SINGLE MEMBER IS DEAD, or has even had a serious illness. On the contrary, so far as can be learned, the members during the past twelve months have been exceptionally healthy and fortunate.” While the group was expecting something terrible to happen because of this brazenly fate-tempting act, nothing did. The Thirteen Club continued meeting for dinners, eventually attracting honorary members that included U.S. presidents.

Whether or not Friday the 13th is inherently unlucky isn’t as much of a concern these days as the fact that millions of people think it is due to the bizarre history around it. According to estimates from the North Carolina-based Stress Management Center and Phobia Institute, the nefarious day can cost businesses up to $800 million in revenue each time it rolls around on the calendar; thousands of people refuse to fly, travel or take any chances on what they see as the unluckiest day of the year. But no matter how you feel about the date, it’s clear that the past still largely influences society’s perception of Friday the 13th — and we can’t blame you if you steer clear of ladders, black cats and mirrors until Saturday.