It’s the Spring of 2022 and we’re in the midst of what feels like the third “lull” of the pandemic. This time last year we were pulling off our masks and donning our “I”m vaccinated” stickers, feeling like the end was in sight. Delta came and went, and in November of 2021 we had another chance to catch our breaths, right before the Omicron surge hit. Now here we are, after another decline in case counts, enjoying another lifting of restrictions. Perhaps people are breathing easier because they believe the end is in sight, or perhaps we’ve all just gotten a bit used to navigating the ups and downs of the last few years. While some of the impacts of the virus — wearing masks and social distancing, for example — will hopefully fade with time, other impacts may persist much longer than most of us would like.

The fear and upheaval that came with the last two years weren’t like anything we’ve ever experienced, but this isn’t the first pandemic to affect the entire world. The Spanish flu pandemic started in early 1918 and raged on until 1920, claiming at least 50 million lives and changing the world forever. With everyone concerned about the future, taking a look at that pandemic’s long-term impacts may give us a glimpse at what we can expect in a post-COVID-19 world.

The Concept of Healthcare Changed Forever

Public health saw some of the most long-lasting impacts from the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. Governments at all levels — national, state and local — were strongly reminded of the biological connections among their community members, thanks to all the diverse ways people interact socially. The virus had the potential to infect just about anyone, so it was critical to ensure everyone had access to health monitoring and care.

As the flu’s impacts started to be felt around the world, countries began to establish health ministries and, in some cases, started to implement healthcare systems based on socialized medicine. On a personal, individual level, the pandemic changed how people viewed their own health and their need for healthcare as well as their need for better access to medical and scientific information. The same is likely to be true in a post-COVID-19 world, as more people pay attention to the health risks in their surroundings each day as well as address their own potentially dangerous health conditions that require treatment.

Although no one was happy with shelter-in-place and quarantine restrictions that were implemented around the world in March 2020, healthcare officials recognized the need to fight the pandemic on a societal level, rather than on an individual level. Those restrictions have continued to be used in an on-again/off-again manner by health officials in response to changing case numbers, and it’s unclear when lockdowns will be fully in the rear-view mirror.

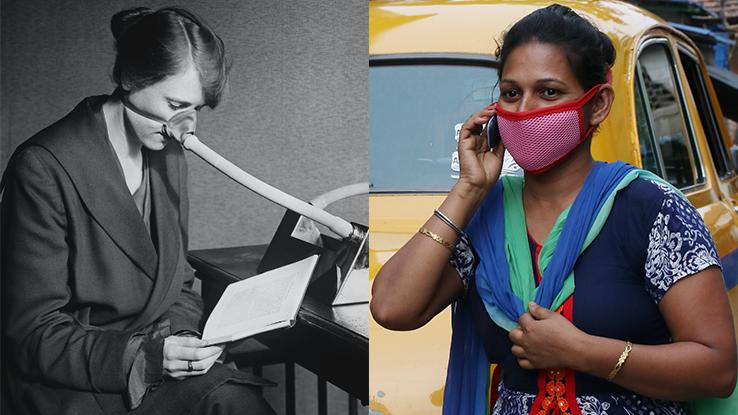

The Roles of Women Took a Giant Leap Forward

The Spanish flu disproportionately affected males at the exact moment in time when men were also being killed in combat during World War I. As a result, the number of women began to exceed the number of men, which made it easier for more women than ever before to enter the workforce and assume leadership roles in various parts of their lives.

By 1920, women made up 20% of all gainfully employed people in the United States. As communities adjusted to seeing women in positions of responsibility, the public view of women began to change. Support for key parts of the women’s movement to grow. It’s no coincidence that the 19th amendment granting women the right to vote had been passed by Congress in June 1919 and ratified in August 1920.

Additionally, the National Federation of Business and Women’s Club was established in 1919. The group’s focus was to eliminate sexual discrimination in the workplace, advocate for equal pay and create an equal rights amendment.

Ironically, the current pandemic may have an equally lasting — but completely opposite — impact on the lives of women. As families began to shelter in place, schools switched to virtual models. Women everywhere took on the role of the teacher in addition to mother. Many had to home-school their children while working from home or still going to work.

A January 2022 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) showed that men had recouped all of their pandemic job losses, while over 1 million fewer women were in the job market compared to pre-pandemic numbers. A 2022 paper from the Brookings Institution paints a slightly different picture, arguing that loss of jobs was driven more by level of education than by gender, but does note that Black women were hardest hit in terms of economic impact. The author also notes that women’s childcare responsibilities increased greatly relative to that of their male caregivers.

Of course, the above statistics are US-centric. A 2021 analysis from the New International Labour Organization reported that “4.2% of women’s employment was eliminated as a result of the pandemic from 2019 to 2020, compared to 3% of men,” and that men were expected to recover those jobs, while the number of employed women is expected to be 13 million fewer than there were pre-pandemic.

One War Ended Early — But the Seeds Were Planted for Another

Many historians believe that the Spanish flu hastened the end of WWI because it took such a huge toll on troops already living in precarious conditions in trenches, barracks and other close quarters. If the flu shortened the duration of the war, then it’s also logical that it could have affected how the war ended. It may even be partially responsible for setting the stage for World War II.

Some experts believe that United States President Woodrow Wilson was a victim of the Spanish Flu and was battling it as he worked to establish the League of Nations and post-war terms with Germany. An article in Smithsonian Magazine indicated that “on April 3, 1919, during the Versailles Peace Conference, Woodrow Wilson collapsed. His sudden weakness and severe confusion halfway through that conference — widely commented upon — very possibly contributed to his abandoning his principles. The result was the disastrous peace treaty, which would later contribute to the start of World War II.”

Other historians have investigated the possibility that Wilson’s confusion was due to a minor stroke, but the symptoms reported by witnesses — high fever, diarrhea, intense coughing, etc. — all fit with flu and not a stroke. Plus, the flu was rampant in Paris at the time, and a young aide of Wilson had already died.

In current times, experts are noticing the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on rising extremism and deepening political divides, especially in countries where political tension was high to begin with. A report from the UN Security Council notes that mitigation strategies across the globe, including lockdowns and increased border enforcement, have become a source of discontent amongst citizens. One UN report notes that extremist groups have been exploiting the frustrations of individuals through disinformation campaigns. While another remarks that “some States have used pandemic-related restrictions to curb dissent by targeting groups (including civil society workers, human rights defenders, and journalists) that raise legitimate concerns.” This combination of increased disinformation alongside a hamstringing of civil society workers and human rights defenders has had significant effects on rising extremism.

Another geopolitical impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been its impact on refugee groups. While refugee groups have largely been spared devastating health outcomes, perhaps due to limited contact with the outside world inherent in refugee camps. However, refugee populations have been impacted in a myriad of other ways, including being left out of socio-economic support efforts. Research shows that refugees across the globe are experiencing food and housing insecurity, while at the same time, the pandemic has reduced the number of aid workers who serve these populations.

The Loss of Life Took a Heavy Toll

It certainly provides some food for thought when you think about the impacts of the Spanish flu pandemic on healthcare, women’s rights and global politics, but the most sobering impact of any pandemic is the loss of life. It’s a harsh dose of reality when you think about the things that could have happened but didn’t because visual artists, musicians, scientists, politicians, writers and millions of people with numerous other talents simply didn’t survive.

One of the most notable works painted about the Spanish flu was completed by Egon Schiele, a visual artist who was at the peak of his career when the flu infected his family in 1918, killing his pregnant wife and then him just a few days later. His portrait of his never-to-be family speaks to the loss of promise he experienced firsthand.

Other notable people who suffered and died from the Spanish flu include Gustave Klimt, sociologist Max Weber and Frederick Trump, the grandfather of U.S. President Donald Trump. It’s tempting to wonder what the world would have been like if these individuals and the millions of others had survived. The Spanish flu’s astounding death toll robbed the world of millions of people who could have changed the world as mothers, fathers, entrepreneurs, teachers, physicians and so much more.

In terms of loss of life, the effects of the coronavirus pandemic will never disappear. Families will never forget the loved ones they lost, and the world’s industries will never know the talent that could have filled their ranks. It will probably take years to sort through the impact on mental health around the world as well. What we do know is that it’s possible to minimize loss and the ongoing impact by doing what we can to prevent the spread of the virus.