Whenever April comes around, and I realize that it’s National Poetry Month, I get a little nervous. I’m a poet, and National Poetry Month makes me think about how fumbling and inarticulate I feel whenever someone asks me what I write poems about, or why I write poems, or what’s so great about poems. It’s not that the questions are unfair, of course; it’s just that I don’t know the answers. I fell in love with poetry at some point in my life, long before I knew what it was or how to make it. I know that poetry matters, but it’s difficult for me to explain how or why.

This year, I’m thinking about that difficulty as National Poetry Month rolls around, and the springtime with it, and we emerge — or, possibly, we don’t emerge — from years of a little more social isolation than we’re used to. We’re changing, and yes, we’re always changing, but at the moment, as a culture, it seems to me that we’re pretty uncomfortable about it. I believe poetry might offer us some tools for embracing change, so I’m going to give that a try here by explaining why the medium matters so much.

Poetry Is Common and Everywhere

First, let’s deal with the problem of our general perception of poetry. We tend to think of poetry as special or unusual, removed from the mundane happenings of everyday life. People read poems at special occasions like weddings and funerals, or they learn about the poems and poets assigned to them in English classes, or they come across bits of poetry memed in faux-inspirational Facebook posts.

I’m not saying that stuff isn’t poetry, but I’m saying it’s definitely not all of it. The earliest forms of poetry weren’t written down but spoken aloud: not on the page, but in the body. Poetry was — and is — closely related to music, which we readily accept is capable of making us feel without necessarily making sense. It’s thought that the earliest poems were cultural attempts to remember what needed to be remembered.

Put all this together, and you begin to understand poetry as an entirely necessary piece of communication. It’s an everyday thing. Like every day of your life, poetry’s full of experimentation and feeling. It’s trying to say what needs to be said but in a way that’s new, full of life, and able to be remembered when we need it most.

Learning What You Already Know

I’ve had the experience now and again of going back to look at something I wrote years ago and realizing that it contains information I’ve been needing. When my grandmother passed away, I happened to find an old poem I wrote that had some lines about acceptance and memory. I’d been feeling overwhelmed and sad about her death, but suddenly my own poem, coming to me from out of the past, seemed helpful. I felt almost like I time-traveled back to the past to make sure I jotted down the thoughts I’d need in the future. Almost.

Poetry is useful in other ways, though. The way we experience the world is completely entangled in the language we use to describe it. That language is largely metaphorical, and poetry is great at coming up with metaphors. When you have lost someone, your heart breaks. When you finally understand something, you see the light. When you’re feeling wonderful, you might even be glowing. These statements are not literally true, but they feel even truer than true. The comparison amplifies the truth.

It’s fortunate for us that language works this way, because it means it’s capable of changing as it adapts to the way we experience the world — as our frames of reference change, and as our available comparisons change. Language adapts whether we resist that adaptation or not, but more and more, it seems to me that we’re afraid of changing. The pandemic, our politics, and a million other things have us using a lot of language about “getting back to normal,” but our ability to change is essential. As the poet Eleni Sikelianos puts it: “Poems maximize the adaptability of language, and, as we know, adaptation is key to animal survival.”

Let Poetry Change Your Mind This National Poetry Month

The rules of language are always a little bit behind the people who use it. Grammatical rules are an attempt to capture a moment in time — to say, “Here’s how we’re doing it now.” We’re alive, though. Once we’ve described “now,” it’s already in the past, and we’ve moved on. Never mind the fact that there are thousands of languages operating with thousands of sets of rules.

This should be both liberating and humbling. We should be free to play around in our language, to manipulate it and alter it and see if we can make it work for us. On the other hand, we can never fully understand it — it’s an organic thing, living and changing in response to the world of which it is a part. Conversations around what pronouns people use make it clear that this stuff produces a lot of cultural anxiety. I wish it wouldn’t, and I think poetry can help.

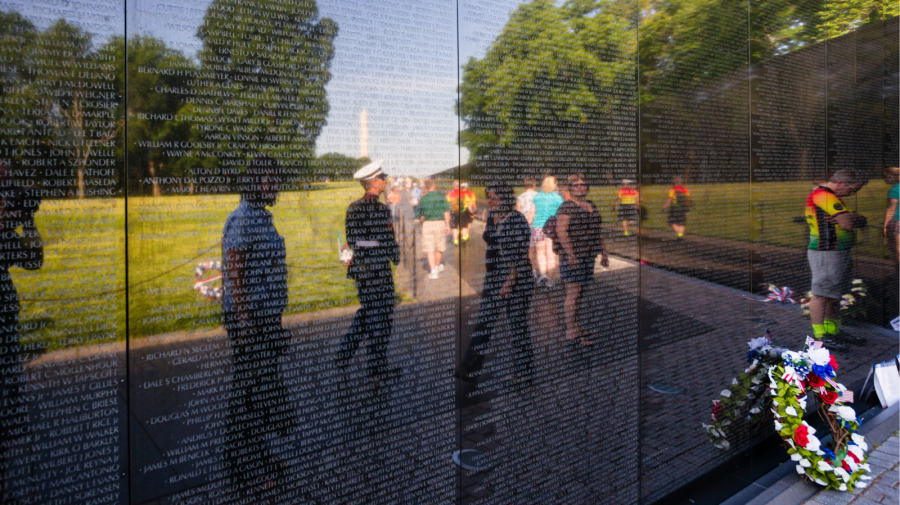

I’ll end with an example from a poem called “Facing It,” by the great American poet Yusef Komunyakaa. In the poem, a veteran of the war in Vietnam is looking at his reflection in the wall of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

At the beginning of the poem, the veteran sees his face in the granite and thinks: “I’m stone.” Then the rest of the poem happens. By the end of it, he thinks: “I’m a window.” It’s not that the pain, or the horrors of war, or the cruelties of life have disappeared, it’s just that the poem embodies a change in the bearing of the person. I think about that a lot — about the importance of knowing both that I can change my mind and that my mind can change. This April, once again, it feels good to be reminded.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman