From dawn until dusk, many of us sneak moments here and there checking our socials. Refreshing our feeds on social media platforms may be the first thing we do in the morning and the last thing we do at night. And it all adds up: On average, according to data from Statista, most people in the United States spend over two hours a day scrolling, liking and perusing. Those two (or more) hours open all of us up to a lot of fun content, sure, but they also expose us to out-of-control amounts of viral headlines, “fake news” and other questionable content that can be surprisingly — and dangerously — influential.

The growing prevalence of fake news on various social media platforms is no secret — nearly a quarter of people in the United States rarely trust the news and other information they read on social media, another Statista survey reveals. But what about the other three-quarters who may put themselves and others at risk by trusting everything they read? This proliferation of harmful fake news is raising the question of how social media platforms can tackle the balance between free speech and false information — and whether those platforms are obligated to do so at all.

The nation is more divided than ever, and it’s largely up to the media to find a way to regulate disinformation. But does doing so run contrary to our free speech rights? To better assess this dilemma, it’s essential to look at how fake news really spreads and affects people, along with whether governments and platforms should mitigate the escalation.

How Does Fake News Actually Spread?

“Spreading like wildfire” is a term that perfectly describes the sharing of fake news once it goes viral. But first it has to gain steam among everyday social media users. Typically, fake news stories start out as deliberate misinformation or as accidentally inaccurate information that someone didn’t fact-check before reposting.

The first type often involves information that purposefully promotes a certain point of view or a person and omits any negative facts, similar to propaganda meant to change the way people think about a subject. The second is often a result of misinterpreted satire or even a snippet of a parody or a joke that people unintentionally take seriously. The difference lies in intent, too: The first type is meant to deceive, and the second is meant to entertain. But both can have similar effects.

Normally, the sharing of fake news starts among smaller groups before reaching increasingly wider audiences on social media. The news first spreads among groups of people with similar interests or among close friends. They repost something on their social media feeds when they find it interesting or shocking or when it reinforces their points of view. Then, curious people and friends of friends may start to repost it to their circles, the members of which then share the news further. Soon, the inaccurate piece of information has reached the masses before it’s been properly fact-checked (or questioned at all).

At this stage, the fake news might go viral. According to Oxford University and the Reuters Institute, social media personalities with large followings are often the culprits. They’re considered “super-spreaders” who can very easily share inaccurate information with their impressionable followers (whom they tend to have a lot of). If you have an extremely active network, you might also frequently come across false information shared between your own friends and family.

How Serious Is the Fake News Problem on Social Media?

To evaluate how powerful fake news is, it helps to look at some examples of incidents when viral news turned out to be complete misinformation. The majority of many of these recent “facts” tend to focus on the coronavirus pandemic and the 2020 election; however, fake news can encompass just about any topic. Below are two examples of viral news that turned out to be factually false.

The Original Claim: An NPR study revealed that 25 million votes cast for Hillary Clinton in 2016 were fake.

The Breakdown: These claims originally came from a website called YourNewsWire, which stated that the report was made by the Pew Research Center — an organization that’s generally regarded as one of the most credible, unbiased polling centers in the United States — with statements cited from an InfoWars article. The source of this information was twisted to fit a narrative trying to invalidate Clinton’s popular-vote victory. It turned out that the original report the fake news was based on was actually made in 2012 and stated that 24 million voter registrations were no longer valid due to deaths or were inaccurate due to voters moving to other states, not that they had voted fraudulently. It had nothing to do with the results of the 2016 election.

The Original Claim: Page 132 of a mysterious Pfizer “vaccine report” stated the vaccine could cause birth defects via genetic manipulation.

The Breakdown: A viral photo shared on social media stated that page 132 of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine safety instructions revealed that the vaccine may lead to birth defects. It was accompanied by a link that took users to the alleged instructions. However, this link only led to documentation from a publicly available Pfizer clinical trial rather than the official government document. Furthermore, page 132 outlined abbreviations, not fertility impact information. Another page contained a brief mention that trial patients should avoid getting pregnant for 28 days after receiving the last dose of the vaccine — common pharmaceutical advice for all vaccines in relation to pregnancies.

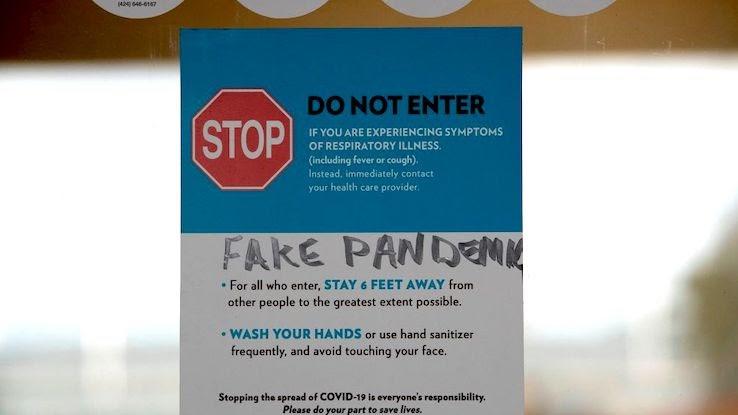

There are costs to this type of fake news; when people believe it and spread it, it can put others in danger. For example, in the case of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation — and fake news about the virus itself — consequences can be dire. BBC reports that, in addition to an unchecked increase in the spread of the novel coronavirus because fake news led people to believe the virus was a hoax, people put their own and others’ lives at risk in various ways as a result of “facts” they learned about COVID-19 on social media. Arson, assaults, attacks and other notable acts of violence occurred, all of which pose “potential health threat[s]” both to believers of the fake news and those who speak out against those who believe it.

What Role Does Freedom of Speech Play?

Fake news clearly has the potential to cause harm. But does that mean the social media platforms where it spreads are obligated to take steps to reduce users’ exposure to potentially harmful information? Many people cite the First Amendment in justifying the argument that social media sites shouldn’t be held accountable for the damaging fake news that proliferates on them.

The First Amendment is a section of the Constitution’s Bill of Rights that protects, among other things, freedom of speech — our right to express ourselves, our ideas and our opinions without being punished for doing so. This makes content regulation a much harder task online. Unless misinformation presents serious harm, the content of fake news is generally protected by the First Amendment. And some people argue it should remain protected because censorship would be a form of oppression and a violation of human rights.

In contrast, those who argue freedom of expression doesn’t fully apply to fake news note that the First Amendment doesn’t necessarily protect an individual’s right to lie or to “intentionally mislead an audience and sway public opinion for political gain,” according to the Center on Human Rights Education. In addition, according to Dr. John L. Vile, the dean of political science at Middle Tennessee State University, “the First Amendment is designed to further the pursuit of truth, [but] it may not protect individuals who…display actual malice by knowingly publishing false information or publishing information ‘with reckless disregard for the truth.'”

While it’s valid to point out the dangers of government censorship, it’s equally important to acknowledge the dangers of spreading false information and to demand change.

What Can Be Done to Regulate Fake News?

It’s clear that fake news can spread quickly — so quickly that it may appear nearly impossible to contain. So what can be done to balance free speech with accountability and potentially stem the flow of all the fakeness? It’s relatively easy, at least on a personal level, to create new consumption habits by making a concerted effort to seek out fact-checking websites — two reliable choices are Snopes and FactCheck.org — and verify a claim’s veracity. But that alone doesn’t stop fake news from spreading.

While social media platforms may not be legally obligated to protect users from fake news, they may be morally compelled to do so. If they can recognize that their platforms, by design, are contributing to the dissemination of harmful media, they should take it upon themselves to place limits on that information. It may not be possible for governments to step in and levy restrictions without compromising or violating freedom of speech — and it may not be their place to do so. “In that case,” states the Center on Human Rights Education, “the onus to address this issue should not rest solely on the government. Corporations such as Facebook and Google should ensure that the entities responsible for creating inaccurate content are regulated appropriately.”

Fortunately, it appears that some sites are working towards this. NBC News reported that, during the second quarter of 2020, Facebook removed 22.5 million posts containing hate speech and 7 million posts “sharing false information about the novel coronavirus, including content that promoted fake preventative measures and exaggerated cures.” This is a step in the right direction, to be sure, but Facebook, other platforms and even media outlets will need to increase these efforts if real change is to be achieved.