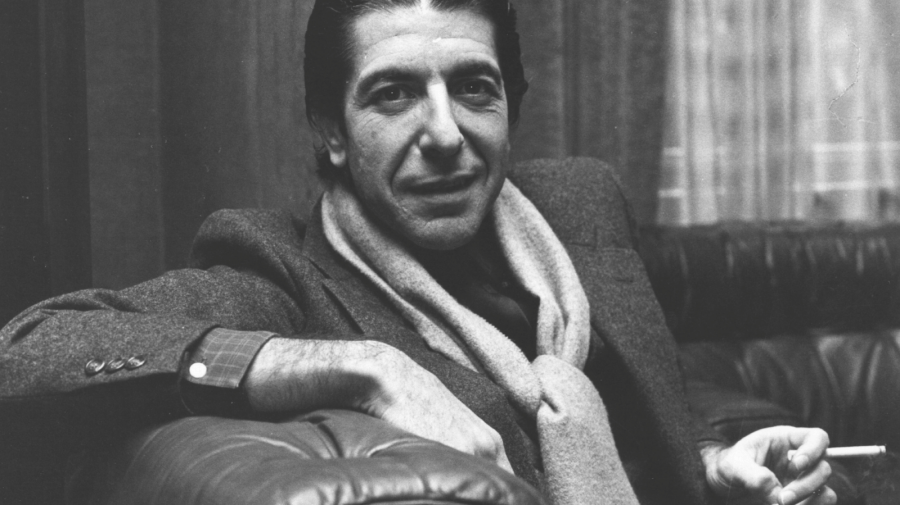

In 1984, Canadian singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen released Various Positions, an album that, perhaps unexpectedly, contained a track that would define his career from then on. Relegated to the record’s B-side, “Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen would go on to be one of the most influential and celebrated songs in the history of music.

Far from being an overnight success, “Hallelujah” was initially overlooked by listeners, but, thanks to its broad appeal, the song’s popularity grew. Not to mention, a particularly persuasive segment of Cohen’s fanbase helped out. Those fans? Other big-name musicians. Now, “Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen is one of the most-covered songs of all time.

That’s kind of the beauty of Cohen’s unlikely magnum opus. It has been countlessly reinterpreted and interrogated by musicians and used to accompany visual works, from live-action films to animated hits. And it all started with a secret chord.

“Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen: The Story Behind the Song

Writing “Hallelujah” was a painful process for Cohen. Reportedly, he penned well over 100 verses of the song as well as countless other notations and revisions. All of this reduced him to a total wreck, driving him to literally bang his head on the floor in frustration. The 1984 version, which clocks in at 4 minutes and 38 seconds, purportedly took him over 5 years to write.

The backbone of the song narrative stems from an Old Testament story in which David performs for King Saul; it also explores the trials and tribulations he faced after striking the infamous “secret chord”. If the composition and arrangement of “Hallelujah” are to be believed, that secret is a key C minor chord progression of C, F, G, A minor, and F.

Regardless, “Hallelujah” has been a kind of Holy Grail for countless musicians who’ve taken a stab at making it their own.

From Cohen to Cale, the Song Finds Its Audience

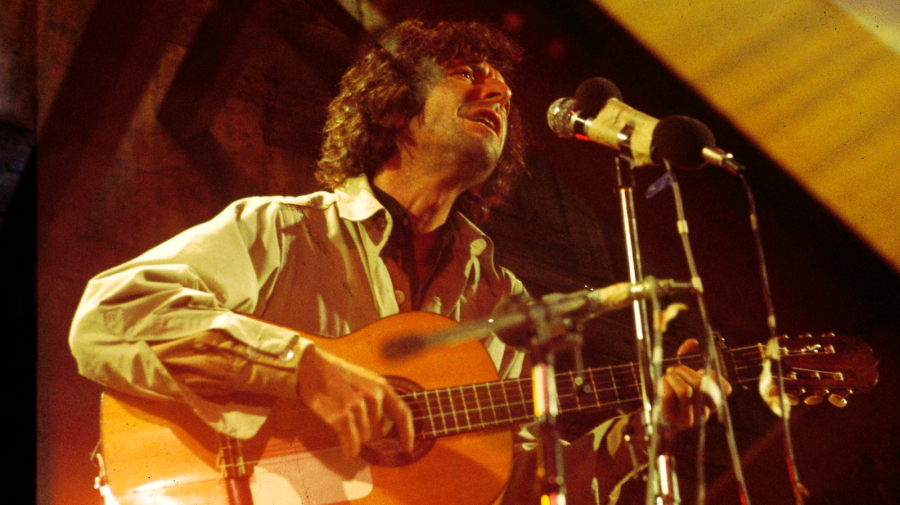

Cohen first recorded “Hallelujah” at 50 years old. At the time, he was struggling to reaffirm his faith in life, “not in some formal religious way, but with enthusiasm, with emotion,” he’d later clarify. An expression of bittersweet joy, the at-once melancholy and joyous song has endured the test of time.

“There is a religious hallelujah, but there are many other ones,” Cohen said (via Pitchfork). “When one looks at the world, there’s only one thing to say, and it’s ‘hallelujah’.”

Despite the acclaim “Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen would eventually attain, the song was initially rejected by Columbia Records. In fact, it wasn’t until John Cale — a founding member of the Velvet Underground — covered the song in 1991 that it received some real attention.

Before Cale’s performance, it was a kind of cult classic song, mainly beloved by Cohen’s fellow artists and a handful of critics. In his now-famous cover that brought “Hallelujah” back into the spotlight, Cale didn’t depart too radically from Cohen. And, although some of the lyrics have changed from version to version and singer to singer, the central sincerity of its original intent remains, no matter who’s behind it.

“Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen: The Song With Many Voices

Many performers have covered “Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen since Cale. By some counts, over 300 covers have been recorded over the life of the song. Perhaps the best-known and most acclaimed version was performed by Jeff Buckley, who tragically passed away just a few years after recording his version.

Fresh, unique interpretations have been performed by a wide variety of talented artists, including U2’s Bono, Neil Diamond, Brandi Carlise, Jon Bon Jovi, k.d. lang and Kate Voegele, among many, many others.

Each cover, no matter who’s performing it, seems to struggle with the song in a special way, as if attempting, in some sense, to transcend the continuous state of disappointment and discouragement the song evokes as the speaker grasps for divinity. Still, so many of these artists give poignant performances that touch fans of all musical genres and tastes.

Before his death in 2016, Cohen expressed amusement at the irony that his song had been so extensively covered and inspired such faith — even though his label, Columbia Records, had no faith in the song, refusing to give it a proper release.

Overuse & Overexposure: “Hallelujah” Goes to Hollywood

A new generation of music lovers were introduced to “Hallelujah” when the DreamWorks film, Shrek (2001), used the John Cale version to score an admittedly poignant scene. The film’s soundtrack replaced Cale’s rendition with one by Rufus Wainwright, making the latter’s cover beloved by a score of new fans. This, of course, sparked debate over which version was superior, Cale’s or Wainwright’s, but that’s kind of a losing battle considering just how many versions of “Hallelujah” are out there.

But Shrek was also just the start of the song’s strange Hollywood journey. Versions of “Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen have since been used in everything from somber ceremonies at awards shows to Saturday Night Live sketches and performances to TV shows like Cold Case and Scrubs.

But it was the use of “Hallelujah” in director Zack Snyder’s Watchmen (2009) that became the proverbial straw that finally broke the camel’s back, proving that a great song doesn’t automatically work with just any set of visuals.

In case you don’t know — and we’re so sorry to break it to you — Snyder used Cohen’s song to score a legendarily bad sex scene between two superheros, Nite Owl (Patrick Wilson) and Silk Spectre (Malin Åkerman). Fans of the graphic novel will know that this adaptation strips the scene of any deeper meaning — it’s kind of just sex for the sake of an R-rated action movie’s ability to show it. The use of the somber “Hallelujah” makes it all somehow worse.

“I can honestly say that this scene in Watchmen was one of the few times I’ve been distinctly and acutely ashamed to be sitting in a movie theater,” Jim Vorel wrote in a piece for Paste about sex scenes gone wrong.

This didn’t completely deter Snyder from ever using the song again in one of his movies. In the “Snyder Cut” of Justice League (2021), he added Allison Crowe’s version of the song to the film as a fitting tribute to his daughter, who tragically passed away during the making of the film.

“Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen: A Lasting Legacy

Despite pop culture’s collective fatigue with the song, it’s clear that “Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen is a song that will endure. Popular with Cohen’s contemporaries as well as today’s artists, what was once destined for the music industry’s dustbin in the ‘80s has had a kind of renaissance that can only be described as miraculous.

While he was struggling to write “Hallelujah”, Cohen couldn’t have known that his struggles would lead to this kind of (eventual) success and appreciation. Now, the song stands as an inspiration to every musician who composes a song that takes time to find an audience, and that’s maybe the best kind of legacy of all.