In 2018, teacher protests swept the country with educators speaking out against widespread public school budget cuts and wage stagnation. Those protests led to strikes, including the Los Angeles teachers’ strike in Grand Park on January 22, 2019, in Los Angeles, California. There, thousands of teachers — and supportive parents and students — celebrated a seeming victory when the United Teachers Los Angeles union and the Los Angeles Unified School District struck a deal that included capping class sizes, providing funding for school nurses and increasing educator pay.

While this victory was significant, it also serves as a testament to the ongoing issues plaguing the United States’ education system. If waves of protestors aren’t enough to convince you of the problems surrounding teacher pay (and other concerns raised by educators), then maybe these shocking numbers will. Salary.com listed $44,926 as the average starting salary for public educators on August 27, 2021. On the other end of the pay scale, top-paid U.S. elementary school teachers make $71,000 annually, while top-paid high school teachers make between $71,000 – $81,000 a year on average. Meanwhile, in Luxembourg, the highest average salary for elementary school teachers is 114,000 euros (or $133,316.16) annually.

Looking at things on a state-by-state basis, New York teachers come out on top, making a median salary of $85,258 (via USA Today) — though New York also requires teachers to earn a master’s degree within their first five years of being on the job, a caveat that can create more barriers for fledgling educators. Other states that compare to New York’s payscale include California, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Alaska, but so many others land on the opposite end of the spectrum, including Oklahoma, where “half of all teachers are [made] less than $33,630 a year” in 2019.

Teachers Spend Their Own Money on Supplies and Hold Second Jobs — but This Shouldn’t Be the Norm

EdTech Magazine asked, “If you were offered a job that paid an average annual salary of $49,000 and required you to work 12- to 16-hour days, would you take it?” Sounds rough, doesn’t it? Well, sadly, that’s the norm for the majority of teachers in the U.S. Teachers spent an average of $745 of their own money on classroom supplies during the 2019/2020 school year. Teachers also paid approximately $252 out of pocket on distance learning materials during the spring of 2020.

To make matters more frustrating, the National Education Association (NEA) found that roughly 16% of teachers held second jobs over the summer, while 20% relied on secondary income year-round in 2019. If at-school secondary jobs are counted — coaching sports, teaching extra courses, helping with extracurriculars — that figure jumps to 59%. The bottom line? Public schools should be funded adequately; teachers should be compensated fairly for all they do. Despite all of this, Education Week legislators scaled back or outright nixed plans to raise teacher pay when the initially pandemic hit.

What It’s Like to Be a Teacher During the COVID-19 Pandemic

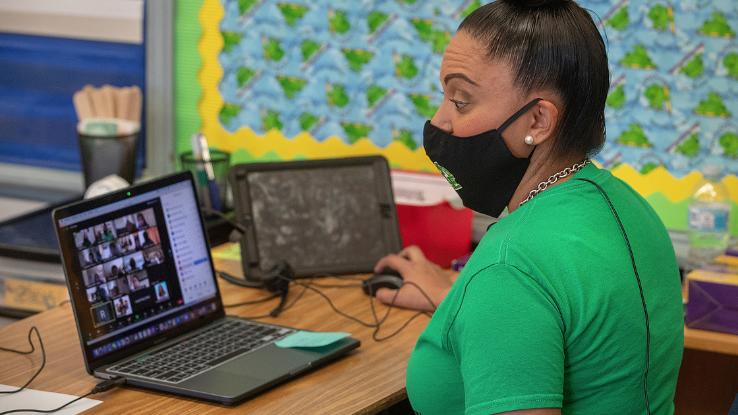

Educators were abruptly thrust into a public health crisis in March 2020. Despite teachers’ best efforts, most schools, especially public schools, didn’t have roadmaps to deal with all-virtual learning scenarios. In fact, plenty of universities and otherwise privately funded schools with seemingly huge endowments weren’t well-equipped either. Between technological roadblocks and the fact that many students don’t have access to computers, tablets or the internet at home, the novel coronavirus pandemic certainly spotlighted discrepancies and shortcomings in the American education system.

In August 2020, the White House formally declared teachers essential workers, noting that they are “critical infrastructure workers” — or, in other words, critical to the infrastructure of reopening the country and bolstering the economy. However, unlike other essential workers, teachers do not always have the training and background to mitigate all of these public health concerns. Funding for PPE and other essential, virus-combating supplies is not always available or particularly abundant. Despite this, educators must potentially risk their health, their families, and their lives to teach their students.

It’s indisputable that teachers are essential members of our communities, but they are also people who, just like all of us, are navigating the horrors of this pandemic. Often, they go beyond the call of their job descriptions — even outside of the classroom. “My students have lost family members, and there’s a lot of trauma we are not addressing,” Jessyca Mathews, an English teacher at Carman-Ainsworth High School in Flint, Michigan, told Time. “When COVID hit, I had kids who were texting me in the middle of the night, and I answered them every single time.”

Mathews is not alone in her dedication to her students. “My colleagues and I have been stressed since spring break because we care, and we’re worried and we know the ins and outs of our jobs,” Kara Stoltenberg, a language arts teacher at Norman High School in Norman, Oklahoma, told Time. “And we know that what the CDC is recommending for in-person learning just isn’t really feasible, considering the lack of funding that we’ve had for a decade.” In states that were more severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers drafted wills and obituaries ahead of the school year.

This is peak dystopian-level disturbing, but, what’s perhaps most disturbing of all is that none of these issues — from teacher pay to how we value teachers’ lives and health — are new. Instead, the pandemic has revealed every crack and fault line in the U.S. education system. It falls on us to reflect on the lessons we’ve learned amidst the COVID-19 and strive to improve American education for teachers and students.