College Athletics in the U.S. is big business. Like, really big. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is an organization of over 1,000 schools in over 100 athletic conferences, and it generates over $1 billion per year on average. That’s just the beginning, though. Early in the pandemic, in May of 2020, ESPN estimated that if the college football season had to be canceled, the loss would be worth around $4 billion.

For a long time, folks have questioned whether this is fair for the athletes who, after all, happen to be the reason for all that revenue. The NCAA, traditionally, has had incredibly strict rules prohibiting athletes from making money from their performance in sports. The size of the revenue streams coming in make that relationship feel a bit uncomfortable in lots of ways, especially when those athletes are playing for coaches who, in many cases, are the highest paid public employees in their states.

It makes sense, then, that at least some of this was bound to change. In June of 2021, the NCAA adopted a new policy allowing college athletes to profit off their name, image and likeness (NIL). Athletes still won’t be paid by their universities, but they will be allowed to accept endorsement deals. There are obviously some gray areas, and we’ll get into those, but it’s clear that this policy is changing things a great deal in major college sports. Let’s take a look at some of the issues, and some of what might change for college athletes.

Ed O’Bannon and How We Got Here

Folks have been concerned about the fact that universities are making profits off the labor of student-athletes for a long time. The NCAA got around those concerns by using the concept of “Amateurism.” Basically, the NCAA requires student-athletes to be considered amateurs, which means they can’t have earned a living playing their sport, they can’t have hired an agent, and so on. Still, the big business of college athletics complicates the concept of amateurism. It’s hard to argue that athletes are amateurs when they spend so much time practicing and playing, and when so many other people are gambling, profiting and earning a living off of their efforts.

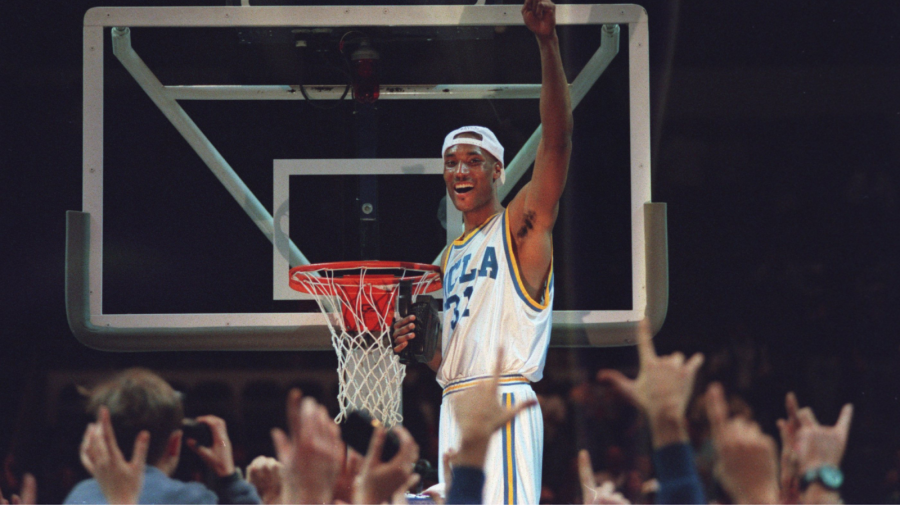

In 2009, Ed O’Bannon sued the NCAA and the Collegiate Licensing Company for violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act and for depriving him of his right to publicity. O’Bannon had been the star of the 1995 UCLA Bruins Men’s Basketball Team that won the National Championship that year on Tyus Edney’s buzzer beater in the final seconds. O’Bannon became the lead plaintiff in the case after he saw his likeness used in the EA Sports video game, NCAA Basketball 09.

We won’t get into the nitty gritty of the legal battles that ensued, but after a series of small steps, we’ve arrived at the ruling that the NCAA has to allow student athletes the right to profit off their name, image and likeness. Beyond that, most people seem to agree that it’s inevitable that eventually college athletes will be paid — it’s just a matter of time.

The Positives of Paying College Athletes

There are obvious reasons why allowing college athletes to at least profit off their name, image and likeness is a good thing. For one thing, other folks are already profiting off the labor of these athletes. Michael Sokolove, who wrote The Last Temptation of Rick Pitino about the basketball scandal at the University of Louisville under the titular coach, pointed out on NPR’s Fresh Air in 2018 that while the men’s basketball program was generating $45 million in revenue, Coach Pitino was making $8 million.

Meanwhile, a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggested that — assuming a collective bargaining structure where the athletes get a 50% share of the revenue was followed — NCAA football players would make an average of $360,000 per year and men’s basketball players would make $500,000. Of course, in reality, the most prominent players would make even more than that. The study suggests that, for example, a starting quarterback on a football team would make $2.4 million.

It’s also the case that top-level athletes in sports like basketball and football — where there is massive earning potential at the professional level — risk injury in playing in college. That means they’re also risking long-term earning potential. According to a study first published in 2013, 67% of Division I college athletes experience a major injury at some point. Maybe even more significant, 50% experience chronic injuries, and that figure is almost two times higher than in non-athletes.

The Downsides of Paying College Athletes

Reasons not to pay college athletes are more based on systemic complications than on fair value. While basically everyone agrees that athletes generate value, questions arise when it comes to figuring out how to build a system that works. Athletes would need programs in place to help them manage money at such a young age, and the NCAA would likely have to allow more open relationships with player agents than what is currently permitted under NIL.

We’ve been talking about football and basketball here, because those are the sports where athletes can make the most money coming out of college. However, both the NFL and the NBA prohibit players from transitioning directly from high school. NBA players must be 19 and one year out of high school. NFL players must be three years out of high school. The NBA, to its credit, has been experimenting with non-college options for players out of high school, but there is still a long way to go, and none of the options carry the same cultural cache as playing college hoops.

It can be argued, as well, that college scholarships themselves do constitute fair value for the majority of college athletes who play in sports that do not generate the massive amounts of revenue that football and basketball do. For example, most of the NCAA’s revenue comes directly from March Madness. It’s unclear what would happen to other NCAA programs if basketball players got their fair share of the value they’re generating. That’s a downside, for sure, but it’s also evidence of a broken system.

Isaiah Wong: A Recent Case Study

Isaiah Wong is a basketball player currently enrolled at the University of Miami in Florida. This past season, Wong played with an endorsement deal from LifeWallet for a reported $100,000. This deal came from John Ruiz, a billionaire who owns LifeWallet and is a huge Miami Hurricanes fan. Ruiz “has struck NIL deals with 111 Hurricanes players to promote either or both of his companies, LifeWallet and Cigarette Racing,” according to the Miami Herald.

Recently though, two things happened. First, Nigel Pack, a basketball player at Kansas State, decided to transfer to Miami. He decided to do this because John Ruiz gave him a two-year endorsement deal with LifeWallet for $800,000 and a new car. Second, Isaiah Wong allegedly threatened to transfer to another school and test the waters about declaring for the NBA Draft if his NIL compensation wasn’t increased (he has since backtracked on this).

You can understand where Wong was coming from. He was the second leading scorer on a team that just made the Elite Eight of the NCAA Tournament, and another player — who was not part of that tournament run — is going to make a bunch of money playing for his university. It’s a messy situation for the NCAA, and it really isn’t clear what the solution is going to be in the long term. What’s clear is that there’s going to be a lot more of this. In the absence of a system where athletes are able to generate fair market value, they are going to try to capitalize however they can. Can you blame them?

Seth Landman

Seth Landman