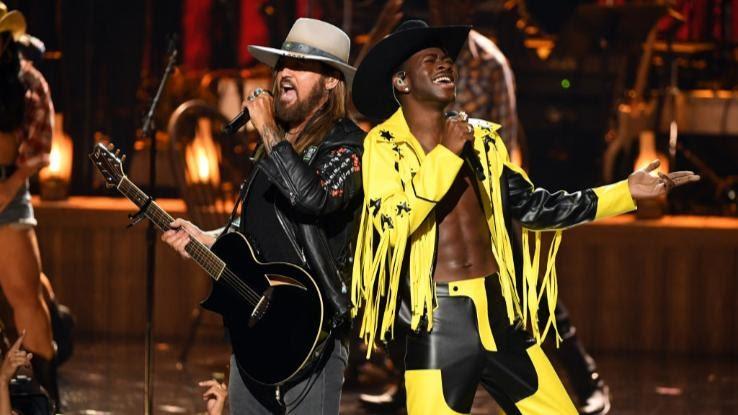

If you’ve been seeing Black musicians in cowboy hats and Western wear filling your social media feed lately, then you may have already gotten a taste of the Yee-Haw Agenda. If you’re not familiar with the term, it refers to a resurgence in country style, music and culture, particularly among African Americans. Think Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” and Beyoncé’s performance of “Daddy Lessons” with the Dixie Chicks at the 2016 Academy of Country Music Awards.

Yet the Yee-Haw Agenda is about a lot more than lassos and wide-open ranges. It’s about challenging the stereotypes people often believe about the American cowboy and country-western music in general. While both have long been associated with white people in the South, the history of Black cowboys in the United States is much richer than many people realize.

Where Did the Yee-Haw Agenda Originate?

The Yee-Haw Agenda got its name from Twitter user Bri Malandro of Dallas, Texas, back in 2018. Malandro recently opened up in an interview about what the Yee-Haw Agenda means to her, as well as what she hopes it will achieve.

“I think it’s important that history is not erased. It was shocking to me that so many people claimed to have never seen Black cowboys before, so creating a place where all of that history could be archived was something that was missing. I believe it has opened up the mind of a lot of people already, based on some of the messages I receive,” Malandro explained.

She’s not wrong. Given the vast array of contributions that African Americas have made to country-western culture, it’s shocking that they have been disassociated with it for so long. While the white cowboy has become a fixture in the minds of many Americans, the first cowboys in the U.S. were actually of Mexican descent, and they were joined by plenty of African Americans during the era of Western expansion, with historians estimating that one in four cowboys was Black.

As The Black West author William Loren Katz explains, “Right after the Civil War, being a cowboy was one of the few jobs open to men of color who wanted to not serve as elevator operators or delivery boys or other similar occupations.” While these early pioneers often faced discriminatory policies and racial prejudice from people in many towns, they became respected members of their own crews.

The Original Black Country Stars

One look back at the history of American music confirms the strong contributions of Black musicians to country music. Even the banjo, which is still heavily identified today with country-western culture, is believed to have originated in West Africa.

Unfortunately, the contributions of many Black artists to the genre are all too often swept under the rug. Among the first was DeFord Bailey, a country music singer and master harmonica player. In 1927, Bailey became the first country star of any race to be introduced on the Grand Ole Opry, right after it officially adopted its new — and enduring — name.

Charlie Pride was another Black country legend who rose to fame during the 1960s and went on to rank second only to Elvis Presley in RCA record sales. When Pride first took to the airwaves, many people didn’t even realize that he was Black. By the time they did, racism wasn’t even a huge factor for once. He had already won the hearts of his fans, and he went on to redefine what it was to be “country” in America.

Although she is often categorized as an R&B artist, Tina Turner’s first solo album was actually titled Tina Turns the Country On!. The record earned her a Grammy nomination, although Grammy executives insisted on placing the blatantly country album in the R&B category.

And who can forget the country contributions of music legend Ray Charles? Charles began his career playing with a country group in the 1940s and went on to release an album called Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music in 1962. Considered by many fans to be one of Charles’ greatest records, the album infused the country with a new enthusiasm for country music.

Black Artists Are Keeping the Legacy Alive

The country-western legacy is still alive and well today among Black musicians who are redefining traditional country stereotypes. Back in 2008, Darius Rucker, a.k.a. “Hootie” of Hootie & the Blowfish fame, decided to make the switch from pop star to country singer. That same year, Rucker released a single called, “Don’t Think I Don’t Think About It”, which went on to become the first debut country single by a Black artist to hit No. 1 on Billboard charts.

In 2018, Jimmie Allen cranked things up a notch with the release of his debut single, “Best Shot.” The song did so well that Allen became the first Black country artist ever to score a career No. 1 with a debut single.

Kane Brown isn’t far behind, as he continues expanding his fan base with country records such as 2018’s Experiment. The record blew up on Apple Music, where it garnered more first-day streams than any other country album in history. And, of course, how could we fail to include another shout out to Lil Nas X, whose “Old Town Road” earned a spot as one of the longest-running Billboard No. 1’s of all time?

Even stars who aren’t traditionally associated with the country genre have been caught dipping into the Yee-Haw Agenda’s Western fashion craze. Texan sisters Beyoncé and Solange Knowles have rocked cowgirl hats and Western garb in their performances along with stars like Lizzo, Cardi B, Azealia Banks, Ciara and Megan Thee Stallion.

As Malandro’s Instagram (@theyeehawagenda) continues to blossom, so does pop culture’s interest in redefining the stereotypical country-western star. Antwaun Sargent, a writer who helped the movement gain traction on Twitter, recently explained why he believes the Yee-Haw Agenda has taken off on social media.

“We’re in a moment where Black cultural producers are being given the opportunity — or taking the opportunity — to reinsert narratives that have been swept under the rug or have not been considered central to our respective industries,” Sargent said. “The Yeehaw Agenda has shown that we have the opportunity to correct narratives in this country.”