It’s been more than 80 years since Amelia Earhart was declared dead in absentia by a court on January 5, 1939. While many years have passed since her disappearance, Earhart’s story still captivates the public imagination. The fate of the most famous woman pilot in aviation history is considered to be one of modern history’s greatest unsolved mysteries.

So what really happened to Amelia Earhart? In recognition of National Amelia Earhart Day on July 24 — the date of her birth in 1897 — we’re taking a look at Earhart’s life, the circumstances surrounding her fateful last flight and the many theories about her disappearance.

Amelia Earhart: A Flight Pioneer

Earhart first became interested in flying at age 23 after visiting an airfield in Long Beach with her father and going on a plane ride. She later recounted the experience in her book “Last Flight” saying: “By the time I had got two or three hundred feet off the ground, I knew I had to fly.” Earhart started working odd jobs to save up money for flying lessons and eventually to buy her own plane.

In 1922, less than one year after her first flying lesson, Earhart set a women’s altitude record of 14,000 feet. She gained a reputation as an excellent pilot in the aviation community, and in 1931, became the first woman to pilot a plane solo across the Atlantic Ocean. This trip catapulted Earhart to celebrity status in the US.

Earhart furthered her career by doing flight stunts, writing books, teaching and designing a line of clothing for women. By 1935 she was known as one of the top aviators worldwide. At age 39, Earhart began to think about settling down and retiring from flying. However, she had one more goal to achieve: becoming the first woman to pilot a plane all the way around the world.

Earhart’s First Circumnavigation Attempt

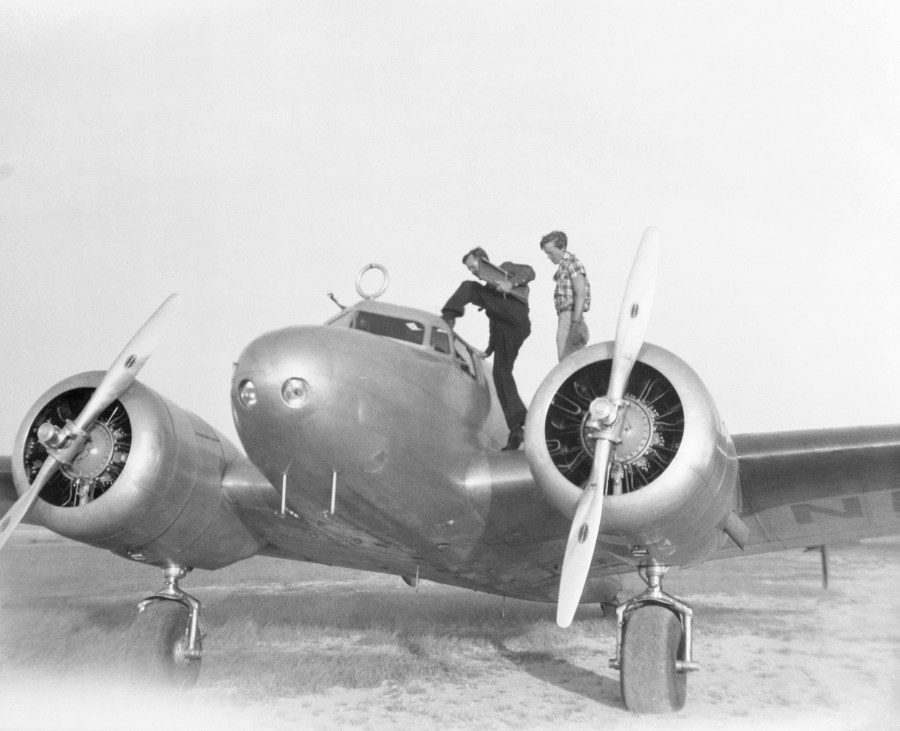

On March 17, 1937, Earhart set out on her first circumnavigation attempt. Her crew included navigators Fred Noonan, Harry Manning and stunt pilot Paul Mantz. They first flew from Oakland, California, to Honolulu, Hawaii, where they stopped to service their plane, a Lockheed Electra Model 10, that had been financed by Purdue University.

After staying in Honolulu for three days, Earhart and her crew were ready to depart from Luke Airfield in Pearl Harbor. Upon takeoff, the Electra suffered from an uncontrolled ground loop, and the front landing gear collapsed. The plane skidded on the runway before coming to a stop, resulting in damage to both the aircraft and the runway.

After this incident, the Electra was in need of extensive repairs. Earhart’s flight around the world was postponed until a later date.

The Second Attempt

Earhart was eager to try again after her first failed circumnavigation attempt. On May 21, 1937, Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan took off from Oakland, California to start the first leg of their trip around the globe. This time, they chose to travel the opposite direction: from west to east.

Their new route was necessitated by changes in weather conditions. This time, Earhart and Noonan planned to first fly from Oakland to Miami, Florida, before making their way across South America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Ocean, hugging the equator the whole way.

Earhart’s Crew

While Earhart’s initial crew included navigators Fred Noonan, Harry Manning and stunt pilot Paul Mantz, Noonan was the only crew member on the second attempt. Noonan was an experienced seaman and navigator from Chicago. Earhart and Noonan had met a few years earlier through mutual friends in Los Angeles.

Noonan had extensive experience navigating over the Pacific Ocean, having previously worked as a navigator for Pan Am. In 1935, Noonan navigated the first round-trip China Clipper flight from San Francisco to Honolulu. He was also responsible for mapping many of Pan Am’s commercial routes across the Pacific Ocean.

Flight Preparations

Because neither Earhart nor Noonan knew morse code, Earhart chose to remove the CW (telegraph code key) from her plane. Earhart also decided to remove an antenna that would have allowed her and Noonan to transmit messages at the 500-kilocycle marine frequency.

While Earhart’s decision to remove this equipment has been the subject of some debate, her decision was a practical one. Instead of using the radio equipment, Earhart was planning on communicating primarily through voice transmission. She believed that the discarded equipment would have amounted to “dead weight” with just her and Noonan onboard the plane.

A Successful Start

After departing from Miami in June, Earhart and Noonan’s flight path took them to Brazil, Dakar, Khartoum, Bangkok and Darwin, Australia. On June 29 they arrived in Lae, New Guinea, their last stop before crossing the Pacific Ocean.

Their plan for the remainder of the flight was to fly from Lae to Howland Island, a sandy uninhabited island midway between Australia and the Hawaiian Islands. A US Coast Guard cutter named Itasca was waiting near Howland Island to guide Earhart and Noonan to the island. They would then continue on to Honolulu and conclude their trip in Oakland, California.

Last-Known Location

Before leaving Lae, Earhart sent a telegram to her husband, publisher George P. Putnam, that read: “RADIO MISUNDERSTANDING AND PERSONNEL UNFITNESS PROBABLY WILL HOLD ONE DAY.” It’s unclear what personnel and radio issues Earhart is referring to in this telegram, but it appears that she was ultimately undeterred; Earhart and Noonan departed for Howland Island on July 2 at 10 a.m. It was the last time that either of them would be seen again.

After Earhart had been en route for about 5 hours, she radioed in to report that she was flying at an altitude of 10,000 ft and was planning on decreasing altitude due to thick clouds. A few hours later, at 5 p.m. Lae time, she radioed in again to report that she was now flying at an altitude of 7,000 ft and a speed of 150 knots. The last confirmed location of Earhart’s plane was near the Nukumanu Islands, about 800 miles into the flight path.

The Approach to Howland Island

Fourteen hours after her departure, the Itasca received a fuzzy transmission from Earhart about “cloudy weather.” The cutter continued to receive increasingly clearer transmissions from the Electra as Earhart approached.

Earhart radioed in again about an hour later, around 6:15 a.m., to let Itasca know that she was approximately 200 miles from the island’s location. She requested that the Itasca use its onboard navigation tool to provide Earhart with a bearing. To facilitate this, Earhart began continuously whistling into the microphone in order to provide the Itasca with a consistent signal.

Missed Signals

At this point, those aboard the Itasca realized that a crucial oversight had occurred. The plan for the approach had been for the Electra to hone in on radio signals from the Itasca, using a radio direction finder (RDF) to determine where the ship’s transmissions were coming from, and to then set a course for the signal. On the approach, however, it became clear that the Electra wasn’t able to receive messages from the Itasca due to issues with its radio equipment.

When Earhart radioed in requesting that the Itasca use its RDF program to get a bearing, those aboard the Itasca immediately realized that their direction finder system couldn’t tune into the plane’s 3105-kHz frequency. The fact that Earhart wasn’t able to receive voice transmissions from the Itasca made matters worse, because there was no way for the Itasca to let Earhart know she needed to broadcast at a different frequency.

Leo Bellarts, the radio operator aboard the Itasca, later recalled that he was “sitting there sweating blood because I couldn’t do a darn thing about it.”

Final Transmissions

With no reply from the Itasca, Earhart continued to send messages letting those onboard know of the plane’s status. At 7:42 a.m., Earhart radioed in saying “CLNG ITASCA WE MUST BE ON YOU BUT CANNOT SEE YOU BUT GAS IS RUNNING LOW BEEN UNABLE TO REACH YOU BY RADIO WE ARE FLYING AT A 1000 FEET.”

This was followed by another two broadcasts from Earhart, both received at 8:43 a.m. The first one was: “WE ARE ON THE LINE 157 337. WE WILL REPEAT THIS MESSAGE. WE WILL REPEAT THIS ON 6210 KILOCYCLES. WAIT.” Earhart’s last-known transmission was “WE ARE RUNNING ON LINE NORTH AND SOUTH.”

Radio Silence

After Earhart’s last radio transmission, the Itasca attempted to signal her plane by using their oil-fueled boilers to generate billowing smoke. Those onboard the ship attempted to signal Earhart and Noonan using both voice transmissions and morse code, but any replies received were either very weak or garbled, and the Itasca was unable to confirm any further communication from Earhart.

Itasca crewmembers speculated that the scattered clouds around Howland Island at the time of the approach may have made it unusually difficult to differentiate the small island from shadows cast on the water. Another possibility was that Noonan’s calculations of their position were slightly off, causing the Electra to search for the island in the wrong area.

The Search for Earhart

Once it became clear that the Itasca had completely lost communication with Earhart, the US Navy kicked off an ambitious search and rescue mission. Planes from the battleship Colorado flew over the area where Earhart was last thought to be, including Gardner and McKean islands and the nearby Carondelet Reef.

By the end of the week, the Navy had searched a huge expanse of the Pacific — over 100,000 miles surrounding Howland Island. The battleship Lexington joined the search party, along with 62 planes.

The search for Earhart ended on July 19, 1937. No physical evidence of Earhart, Noonan or the Electra 10-E was found.

Citizens Continue the Search

While the official search mission concluded shortly after Earhart disappeared, the unofficial search is still far from over. Perhaps because no physical evidence of the plane or its crew was ever found, or due to Earhart’s popularity, the public has continued to question what became of Earhart and Noonan.

Theories on their disappearance range from the plausible (a crash landing after the plane ran out of gas) to the laughably absurd (they were taken hostage by the Japanese military). Amidst the ongoing mystery of her disappearance, one thing can be said for sure: The American public continues to be captivated by the story of Amelia Earhart.

Here are some of the leading theories about what exactly happened to Earhart on July 2, 1937.

The Electra Crash-Landed in the Pacific

The theory that Earhart’s plane simply ran out of fuel while she and Noonan were searching for Howland Island is seen as the most plausible. Her last messages to the Itasca indicated that she was running dangerously low on fuel, and there weren’t many other landmasses for the Electra to safely land on.

Additionally, this theory is supported by the official explanation the US Navy settled on when concluding their search of the area. Because it took a few hours for the search and rescue mission to start in earnest after loss of radio contact, experts have speculated that the Electra could have been broken up by ocean waves shortly after the crash. Of course, this would mean that Earhart and Noonan most likely drowned in the Pacific following the crash.

The Plane Landed on Another Island

An alternate theory suggests that Earhart was able to land safely, but on a different island than planned. The International Historic Aircraft Recovery Group believes that Earhart landed safely on Gardner Island, a sandy strip of land now called Nikumaroro.

This theory is supported by some evidence. In 1940, bones were discovered on the island — including a human skull. While the bones were originally examined in Fiji and thought to have belonged to a middle-aged man with a stocky build, a second look at the measurements taken from the bones in 1998 determined that they most likely belonged to a “tall white female of northern European ancestry.”

The Jaluit Harbor Photograph

In 2017, a discovery in the National Archives led many to believe that Earhart had landed safely on nearby Jaluit Island. The photograph, which was discovered by a retired federal agent, depicts Jaluit Harbor with several individuals standing on a pier. Facial recognition experts have determined that two people in the photograph are good matches for Earhart and Noonan.

This photograph led many to believe that Earhart and Noonan landed safely on Januit island and were taken prisoner by the Japanese government shortly after. However, this theory lost credibility when the same photograph was found in a textbook that had been published two years prior to Earhart’s voyage.

Despite knowing that the photograph does not depict Earhart and Noonan, many people still subscribe to the idea that Earhart was taken prisoner by the Japanese government.

Earhart Was Taken Prisoner by the Japanese

The theory that Earhart was a Japanese prisoner is still popular to this day, despite the fact that very little evidence exists to support it. The idea was first proposed in the 1960s and was supported by the book “Amelia Earhart Lives,” written by former Air Force major Joseph Gervais.

Gervais proposes that Earhart was on “a spy mission for President Roosevelt, interned in Japan during the war and traded back to the US in 1945, where she has lived under an alias ever since.” The Japanese government denies having any contact with Earhart or Noonan.

Earhart Was a US Spy

In his book, “Lost Star,” Randall Brink argues that Earhart and Noonan were never actually supposed to land at Howland Island. Brink asserts that Earhart’s circumnavigation attempt was a cover for her work as a US spy. His theory is that the purpose of Earhart’s trip over the Pacific Ocean was to identify and monitor Japanese island military installations and report back to the US.

According to Brink, Earhart’s mission went awry when her plane was noticed and either shot down or forced to land by the Japanese. This theory remains popular to this day, despite the lack of evidence to support its claims.

Earhart Took an Alternate Identity

Even less plausible is the theory put forward by author Joe Klass — that Amelia Earhart was first captured by the Japanese, held prisoner, eventually rescued by US forces and returned to the US under a different identity. Klass promoted the theory that Earhart, tired of the spotlight, chose to take on a completely new identity: as housewife Irene Bolam.

This theory was built on the fact that Irene Bolam and Earhart looked similar and that Bolam also had a pilot’s license. The issue with this theory, however, was that Bolam adamantly denied it. After the book was published by McGraw-Hill, Bolam sued the publisher, and the book was pulled from the shelves.

Despite the book being out of print, Earhart enthusiasts are still interested in it, as it provides one of the most comprehensive accounts of Earhart’s disappearance and logically integrates the found evidence.

She Was Abducted by Aliens

Hands down the craziest theory on Earhart’s disappearance is that on the day she disappeared, she made contact with an alien spacecraft, and was either shot down or abducted. This theory persists despite the fact that its origins are unclear, and there is absolutely no evidence to support it.

This theory was covered in an episode of “Star Trek: Voyager,” in which the Voyager crew stumble upon a group of people who were abducted by alien life forms in the year 1937, including Amelia Earhart. In the episode, Earhart had been captured by the aliens and taken to another planet where she was held in a cryostasis chamber, artificially prolonging her life.

Film and Television Coverage

“Star Trek: Voyager” wasn’t the only TV show to include a plotline about Earhart. The true crime series “In Search Of” devoted an episode to the mystery of Earhart’s disappearance in 1976. After the episode, titled “In Search Of Amelia Earhart” premiered, a number of documentaries about Earhart debuted. One of these was the PBS documentary “Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage.”

In the 1994 film “Amelia Earhart: The Final Flight,” Diane Keaton starred as Earhart alongside Rutger Hauer and Bruce Dern. The film was first released on television and later had a theatrical release. Actors Amy Adams and Hilary Swank have both portrayed Earhart on the big screen; Swank was the star of the 2009 biopic “Amelia,” and Adams played Earhart in 2009’s “Night at the Museum 2: Battle of the Smithsonian.”

Will We Ever Really Know What Happened?

While Earhart’s disappearance has been the cause of much speculation and debate, it’s possible that we will never really know what happened to her and Noonan after they departed from Lae, New Guinea.

Shortly before Earhart’s last flight, she wrote in a letter to her husband: “Please know that I am aware of the hazards. I want to do it because I want to do it. Women must try to do things as men have tried. When they fail, their failure must be a challenge to others.”