As you might know, May is annual Mental Health Awareness Month — a time that gives us space to discuss mental illness and prioritize our mental health. One of the great things about film, and art in general, is the way it can move the needle or start necessary conversations. When it comes to mental illness, on-screen representation matters. That shouldn’t be a surprise. What might be shocking, though, is just how lacking representation is, even in 2022.

According to a study conducted by the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative (USC AII) and published in May 2019, “Out of 4,598 speaking characters across the 100 top films of 2016, only 76 [or 1.7 percent] were depicted with a significant or persistent mental health condition.” As the study points out, this is a stark contrast with our reality: roughly 20 percent of adults in the U.S. live with a mental health condition and/or mental illness. To make matters more frustrating, when characters with mental illnesses are depicted, the portrayals often reinforce harmful stereotypes.

Still, art has the propensity to dismantle the stigma and stereotypes surrounding mental illness. Accurate, nuanced depictions of mental illness and disorders can help people living with those conditions feel seen and less alone. Additionally, films that center mentally ill characters can educate others, help us build support systems and dispel harmful misinformation. Here, we’re looking at some films that harness that potential. But first, what has Hollywood been getting wrong for so long?

Editor’s Note: This article contains mentions of various mental illnesses and mental health disorders as well as discussions of how some of these illnesses and disorders are portrayed, both accurately and poorly, in film. Additionally, while the films selected later on in the article depict mental illness and mental disorders accurately for the most part, it’s important to note that these depictions may not resonate for some readers as everyone’s experience with mental illness and mental health disorders is nuanced and specific.

Why Is It Important to Accurately Depict Characters With Mental Illness?

In both film and TV, mental health is often stigmatized, used as a plot device, or trivialized. You know, made into a character “quirk” instead of being taken seriously. The study mentioned above found that of 87 film characters who have mental health conditions or mental illness about 47 percent of characters were disparaged; 22 percent of characters’ mental health conditions or mental illness were met with humor; and 15 percent of characters felt the need to conceal their mental health condition or mental illness.

Moreover, when characters with mental illness are portrayed on screen, 46 percent of them were found to be perpetrators of violence. Regardless of intention, most films and shows normalize name-calling, with characters slinging words like “psycho,” “crazy,” “freak,” “silly,” “nuts,” “weird” and “monster” at other characters who outwardly express a mental illness.

The study also shows that when there is representation, it’s not reflective of most audience members’ identities or experiences. For example, while 20 percent of teenagers in the U.S. experience a mental health condition, only 7 percent of film characters (of that 87) were teens.

Further Disparities in Mental Healthcare & On-Screen Representation

Mental Health America found that 6.8 million Black Americans report having a diagnosable mental illness, but, despite this fact, only 11 of the characters with mental health conditions surveyed by USC AII were Black. This trend of underrepresentation continues for all people of color: Only four of the characters in the survey were Asian people; only one character was a multiracial person; and none of the characters identified as Hispanic, Latinx, Middle Eastern, Native Hawai’ian or Pacific Islander, or as Indigenous or First Nations peoples.

Additionally, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) has found that LGB adults are more than twice as likely as straight adults to experience a mental health condition. Not to mention, LGBTQ+ people are at a higher risk than cis and/or straight people for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. But portrayals of mental illness often leave out the LGBTQ+ community as well — especially when it comes to trans and nonbinary characters.

Out of 50 TV shows surveyed by USC AII, just eight LGB characters experienced mental health conditions, while the transgender community wasn’t represented at all. And, out of 100 films, none of the characters with mental health conditions identified as being part of the LGBTQ+ community.

All of this is to say that, in addition to stigmatizing mental illness, on-screen depictions often don’t account for the multifaceted experiences of most folks, nor do these depictions account for the way the aspects of an individual may intersect. There’s hardly any accounting for diversity in race, gender or sexual orientation at all, nor is there an attempt to understand how those intersections of identity may interact with mental health conditions or illness.

Common Onscreen Faux Pas

In order to shift how stories portray characters with mental health conditions and mental illness, USC AII suggests that writers ask themselves a very fundamental question: Why am I telling this story? This can help creators avoid common pitfalls, like depicting unnecessary stigma, using a mental health condition as a plot device, and/or making mental illness into the punchline.

To be frank, the lived experiences of folks who have mental health conditions and illnesses are missing from popular culture. And, when these experiences are depicted, they’re often displayed irresponsibly: Netflix’s series 13 Reasons Why was heavily criticized for its depiction of death by suicide, an act that’s often romanticized or shown as “the only choice” a character can make.

As in life, medication is stigmatized, with characters eschewing treatment because it inhibits them in some way — such as the old trope of an artist who can’t create because they feel blocked by their medication. Moreover, because mental health conditions and illnesses are stigmatized and often associated with shame — a dark secret a character must hide or can’t talk about — they often aren’t surrounded by any sort of support system.

And then there’s the association between mental illness and violence that’s particularly prevalent in the horror genre, which derives scares from our very human fear of the “unknown” or the “unfamiliar.” For example, in Alfred Hitchcock’s classic Psycho, a movie that spawned countless slasher films, the main character, serial killer Norman Bates, is given a “diagnosis” by a psychiatrist, who cites a “split personality” as the source of Bates’ violent tendencies. “When the mind houses two personalities, there is always a battle,” he says. “In Norman’s case, the battle is over and the dominant personality has won.”

A writer for Resources to Recover states that although the Academy Award-winning A Beautiful Mind “may have done more than any other popular movie to combat stigma and draw attention to the positive contributions of people with serious mental health disorders,” it still misses the mark, prioritizing a Hollywood twist over the reality of schizophrenia.

Another acclaimed miss? Silver Linings Playbook. While the dramedy, which centers on two characters with bipolar disorder, may depict the toll mental illness takes on individuals and families in a more realistic, nuanced way, it misses the mark by going the “cure” route, instead of reiterating that mental illness is about management. When the main characters get together, finding love feels inextricably linked to their mental well-being.

Perhaps this speaks more to the limitations of film and the need for resolution. But, limitations or not, this sort of resolution perpetuates the idea that something is “wrong” with the characters and that they can heal one another if they just try hard enough.

Movies That Depict Mental Illness (Mostly) Well

Inside Out (2015)

In this landmark film from animation giant Pixar, a young girl named Riley (Kaitlyn Dias) deals with depression when her family moves from Minnesota to San Francisco. The film personifies the emotions that exist inside Riley and influence how she presents herself to the outside world. Two of those emotions, Sadness (Phyllis Smith) and Joy (Amy Poehler), drive the plot.

By her nature, Joy just wants to find a way for Riley to be happy again before she completely shuts down. On the outside, Riley represses her emotions, lashes out at her parents and tries to run away. In the end, Sadness convinces Joy that it’s more than okay to be sad sometimes. It’s actually better to feel sad, to talk about those feelings, than to mask them with faux-happiness.

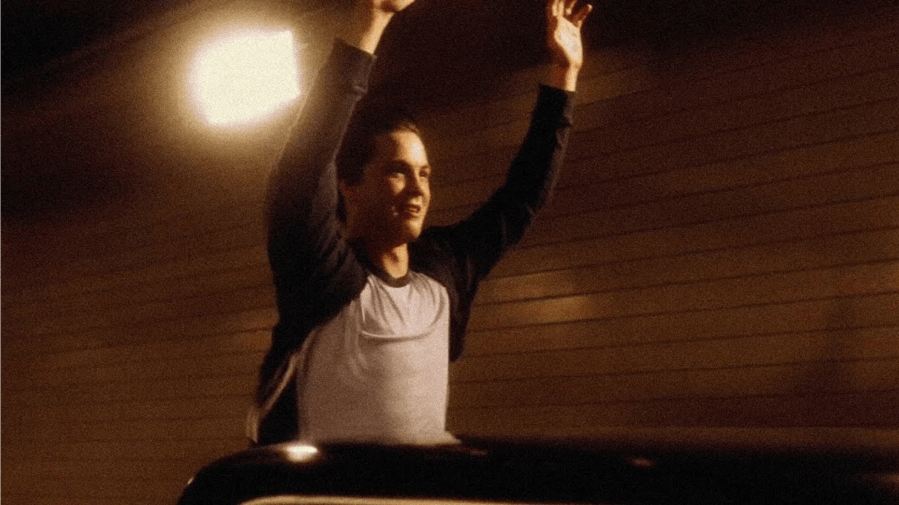

The Perks of Being a Wallflower (2012)

Writer Stephen Chbosky decided to adapt his seminal young adult novel into a film because he feels it’s “harder to feel alone if you see dozens of people around you laughing and crying or nodding their heads at the same issues.” It also helps that the film depicts the main character Charlie’s (Logan Lerman) depression in a nuanced, genuine way: Charlie makes new best friends and shares real happiness and laughter with them. What he doesn’t share? Everything that’s bottled up inside of him.

The film has also received praise for how it portrays post-traumatic stress insofar as Charlie is navigating his memories of childhood sexual abuse in addition to a depression that those around him link to other events in his life. Moreover, Charlie’s romantic relationship with Sam (Emma Watson) doesn’t magically fix or save him; instead, she’s just one part of his support system and helps him, boundaries intact, to navigate his mental illness.

Melancholia (2011)

The film’s director has said the aptly-titled Melancholia stems from his own experiences with a depressive episode, but, even more so, it’s the execution of this movie that really resonates. The story centers on two sisters, Justine and Claire, played by Kirsten Dunst and Charlotte Gainsbourg respectively.

While Justine prepares for her wedding, she navigates her depression — as well as the fact that a rogue planet is set to collide catastrophically with Earth. Often, it’s difficult to capture depression on film or in writing, but Melancholia‘s pervasive sense of impending doom, of lethargy, feels like an apt way to portray the protagonist’s mental health disorder.

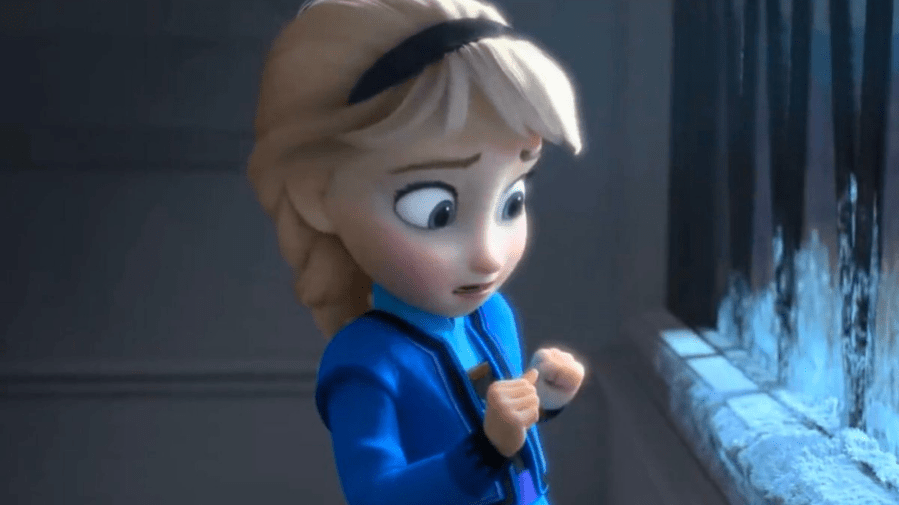

Frozen (2013)

Sure, Frozen has an anthropomorphic snowman and a wildly catchy song that our brains just can’t let go of, but Elsa (Idina Menzel) and her ice powers are also the perfect metaphor for dealing with anxiety and depression, which director Jennifer Lee says is no coincidence.

After hurting her sister with her ice powers as a child, Elsa locks herself away in her room and lives by the mantra “conceal, don’t feel”. For Elsa, her past mistake means she deserves isolation. In the end, Elsa learns that must manage her emotion-fueled powers instead of trying to hide them.

Horse Girl (2020)

Called an “unorthodox” take on mental illness by IndieWire, Horse Girl stars Alison Brie (Glow, Promising Young Woman) as Sarah, a young woman who finds her day-to-day life uprooted after her dreams seem to spill into her real life.

As the film progresses, the audience learns that Sarah’s family has a history of mental illness, which makes her, at times, unwilling to trust what she’s seeing or thinking. Unlike other thriller-like films that toe that not-quite-sure-what’s-real line, Horse Girl feels more intentional.

Not only is the film anchored by Brie’s strong performance and a Charlie Kaufman-esque narrative structure, but it’s informed by the star’s own lived experiences. Calling it “quite a personal project,” Brie explained that her character stems from her own family history.

“My mother’s mother lived with paranoid schizophrenia and I grew up hearing stories about her and my mother’s childhood and just knowing that mental illness existed in my bloodline,” Brie told IndieWire. “The older I get and the more I have my own bouts of depression and struggles I become acutely aware that this [mental illness] is in my DNA.”

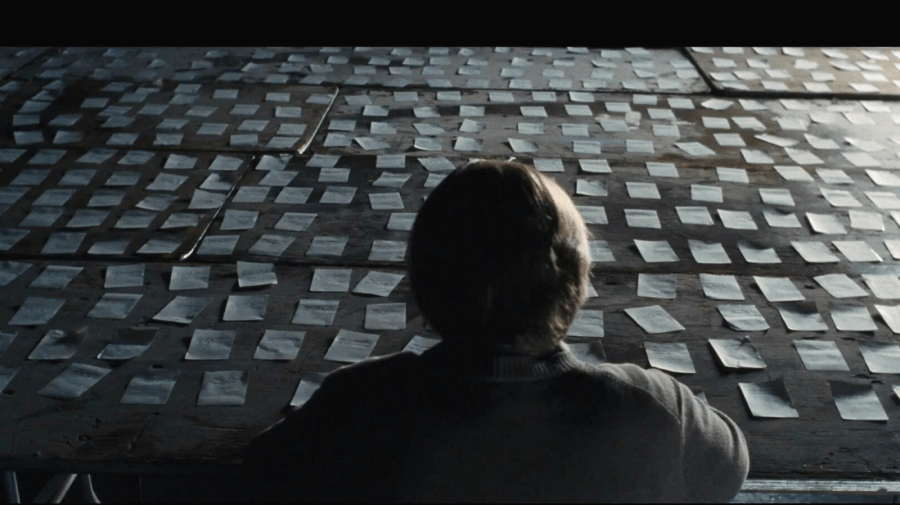

Synecdoche, New York (2008)

Speaking of Charlie Kaufman, the writer-director’s postmodern film, Synecdoche, New York, never puts a name to what its protagonist, Caden (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is experiencing, but it does resonate as a depiction of mental illness in some ways. Caden, a theater director, attempts to stage an increasingly elaborate show.

In fact, the attempt goes on for years and years because he can’t quite get his magnum opus right; doppelgängers, akin to folks in his shrinking personal life, populate the cast and crew; and, in general, his dedication to depicting realism end up blurring the lines between his play and his life.

It takes the Shakespearean notion of “a play within a play” much further. We see Caden strive for perfectionism, deal with intrusive thoughts, and grapple with the anxiety surrounding how others perceive him and his work, all of which feel akin to how some individuals experience obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), even if the film never names it.

Looking for more quality representation? Check out our related roundup, 11 Shows That Depict Mental Illness (Mostly) Well.