I watched Happening — the Audrey Diwan directed and co-written film about a 23-year-old woman desperately seeking to terminate her unwanted pregnancy in 1963 France — the day after Politico reported about the Supreme Court leaked draft and their intention to overturn abortion rights in the US. Happening opens exclusively in theaters this Friday, May 6.

It wasn’t an easy watch. I felt for Anne (Anamaria Vartolomei). I saw myself in her. She’s a bright university student with a future ahead of her and an easy way with words. Her parents own a bar and are proud of her. She’s studying literature and talks about Sartre and Camus over lunch with her friends. She’s about to graduate with honorable mentions and is a favorite among teachers — until she realizes she’s pregnant.

Her doctor is sympathetic but he can’t help her. The law is unsparing, he tells her. Anyone who helps her could end up in jail. Anne could end up locked up as well. Abortion was illegal in France until 1975 with the passage of the “Loi Veil,” pushed by then Minister of Health Simone Veil.

Anne’s story shows the crudeness of the time. She goes to any length to make sure she still has a future. “I’d like a child one day, but not instead of a life. I could hate the kid for it,” she tells her doctor after an attempt to terminate the pregnancy herself. She inserted a knitting needle into her vagina and uterus. We also see how abortionists operating in the shadows had to introduce probes into women’s uteri to try and stop pregnancies, putting their lives at risk sometimes. No anesthetics were used.

“Only such disturbing images can make us aware of the horrors that were perpetrated on women’s bodies, and what a step backwards would mean,” writes author Annie Ernaux in a letter relating her reaction after watching Happening. The film is based on her own experience as a promising young woman in France in the 1960s and the book she wrote about it.

Be aware that watching Happening is gutting. It’s a movie told entirely from Anne’s point of view. You get to walk in her shoes and feel the desperation as the weeks go by and she sees her ambitions of becoming a professional woman disappearing.

One of Anne’s teachers wants to know whether she’s been ill — she hasn’t been paying attention in class and her assignments have been lacking. “The kind of illness that only strikes women and turns them into housewives,” she tells him as a way of explaining what happened without uttering the word “pregnant.”

Happening made me think about my own younger years figuring out life, studies and sex in the late 1990s and early 2000s. I was luckier than Ernaux or her film alter ego, Anne. Abortion was legalized in my natal Spain in 1985, ten years after the dictatorship ended. There was a somewhat controversial 1990 TV commercial — paid for by the Spanish government — advocating for the use of condoms among teenagers and young adults. Sexual education was very much part of the curriculum for middle and high schoolers. Access to Plan B pills was a free doctor’s visit away, even if doctors could be judgy sometimes. I had access to the education and healthcare necessary never to be in Anne’s distressed and dangerous position.

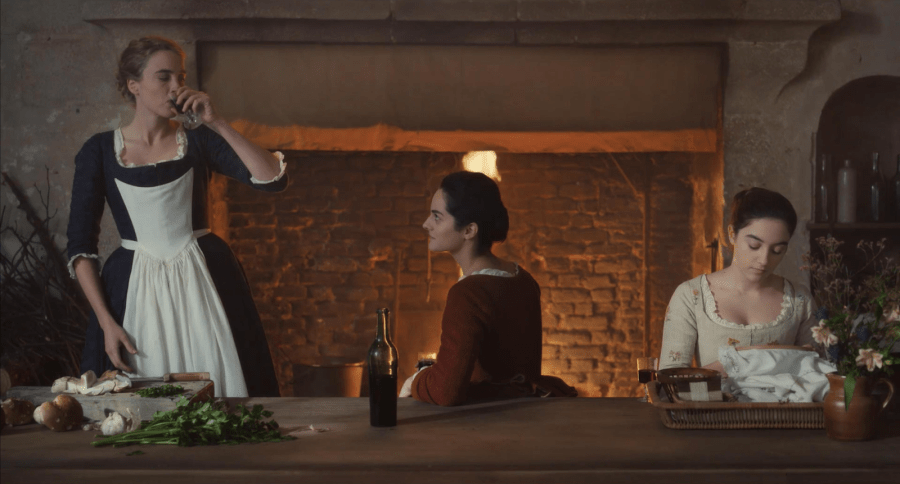

Yet hers isn’t an uncommon predicament. Those of us who menstruate are put in a vulnerable situation when access to contraception and reproductive healthcare is denied, expensive, unavailable or simply illegal. Céline Sciamma’s 2019 film Portrait of a Lady on Fire tells us how it was done in the 18th century. She depicts an abortion in the movie with fierceness and a complete lack of judgment for her characters.

In the film, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), the maid, hasn’t had her period in three months. Marianne (Noémie Merlant), the painter, asks her whether she wants a baby. Sophie says no. The next morning Marianne and Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), the lady the painter is falling for, make Sophie run on the beach until she’s out of breath and collapses on the sand. She also climbs to a beam on the ceiling, grabbing it and leaving her legs hanging in the air. The three women collect herbs and brew them into an infusion that Sophie drinks. Nothing works. In the end, they take Sophie to the village’s herbalist and she performs an abortion. The camera is on Sophie’s face. You can see her pain — you can feel it.

We’ve come a long way since 1770 and what Sciamma sketches in Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Yet the story of Sophie — and Anne’s in Happening — was told again in Never Rarely Sometimes Always. The 2020 film is written and directed by Eliza Hittman and follows Autumn (Sidney Flanigan), a present-day 17 year old who finds out she’s pregnant and travels from rural Pennsylvania to New York City to seek an abortion since Pennsylvania requires parental consent for the procedure. Fortunately, Autumn’s cousin and best friend Skylar (Talia Ryder) accompanies her on the costly and difficult journey. We never know how Autumn became pregnant — the film suggests she may be an incest survivor — which makes it even more poignant in advocating for the need for free and easy access to this kind of healthcare for teenagers and adult uterus-havers anywhere.

Then there’s the neo-western Little Woods, written and directed by Nia DaCosta. The 2018 film adds to the tale of Anne, Sophie and Autumn. In this case, it’s Deb’s (Lily James) story. She’s a single mother and waitress living in a tent city. When she finds out that she’s pregnant again and that her late mother’s house is about to be foreclosed on, she doesn’t have many options. She doesn’t want the baby and, with no health insurance, she can’t afford the $8,000 for prenatal care. Her sister Ollie (Tessa Thompson) is forced to deal drugs to help her. Ollie smuggles Deb into Canada. It’s easier to get an abortion there than to travel hundreds of miles and pay for one in the US. Deb had even considered having an illegal abortion close to her home in rural North Dakota to avoid the long trip.

I’ve always believed in the power of film as a way of teaching us about other people’s existences and struggles, as a tool that allows us to live for a couple of hours in someone else’s skin.

I understand there’s a big Marvel tentpole movie vying for everyone’s eyeballs opening this weekend in theaters. But if you decide to go to the movies, maybe give Anne’s very humanizing story a try instead and go watch Happening. Or just stream Never Rarely Sometimes Always (Amazon Freevee), Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Hulu), Little Woods (Hulu), Plan B (Hulu) or Unpregnant (HBO Max). Get nostalgic even and rewatch Dirty Dancing (HBO Max). They’re all excellent reminders of how vital access to contraception and abortion are for so many of us.

You can also read our article on who would be most impacted if Roe v. Wade gets overturned.