Our desire to wonder about and explore the universe is ancient and endless. Even prehistoric cave art, in many cases, contains evidence of human curiosity about the cosmos. On the other hand, space travel is an extremely new phenomenon for us here on planet Earth, cosmically speaking.

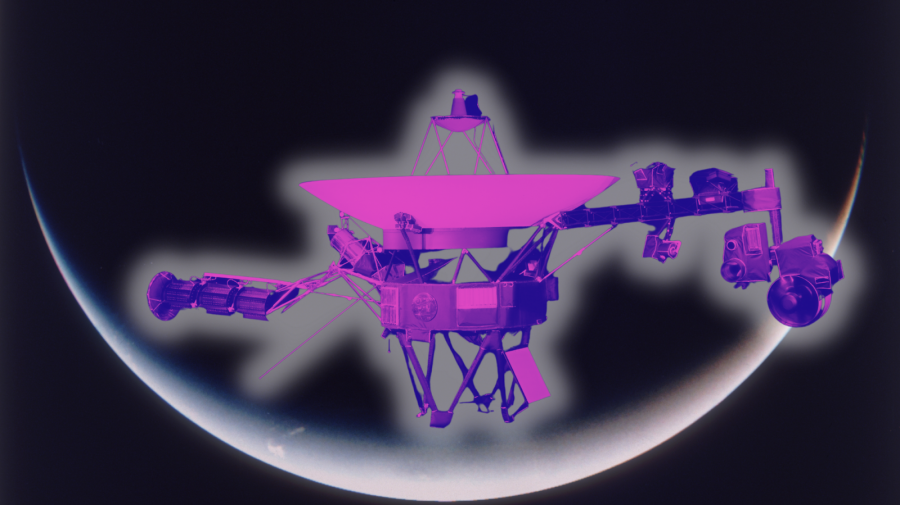

NASA’s Voyager program is one of the most important instances of space exploration in the long history of that very ancient human desire. When NASA sent Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 out in the 1970s, the mission was simple: explore Jupiter, Saturn and the moons of those two planets. The probes were originally designed to last just five years. And yet today, 45 years after they were launched, they’re still hurtling through interstellar space, at a greater distance than human-made objects have ever been from Earth. How is that possible, and why is it important?

The Amazing Optimism of Voyager and the Golden Record

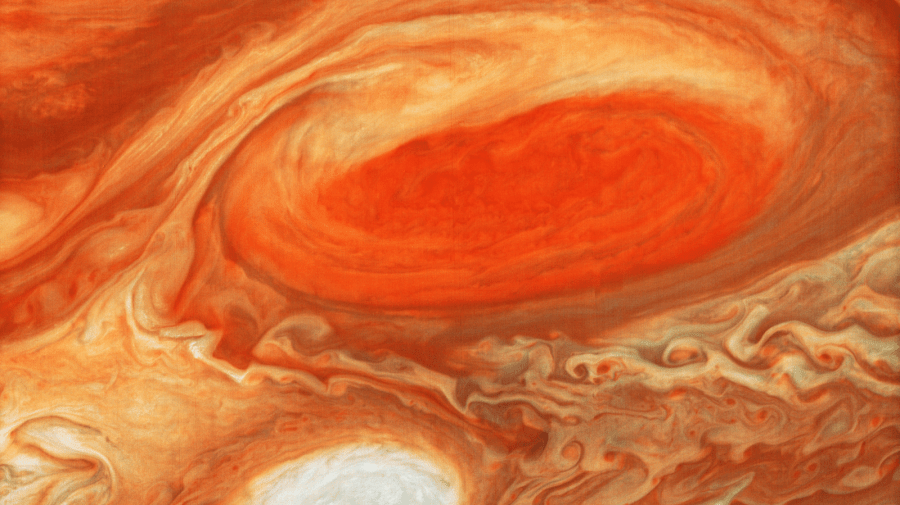

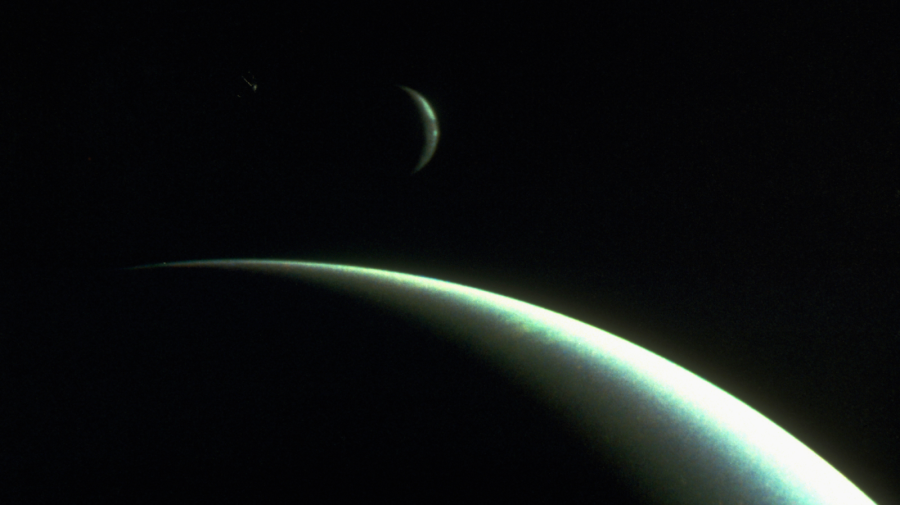

Despite the initial plan to explore just Jupiter and Saturn, the folks who planned the Voyager mission did have larger goals than that in mind. For one thing, four planets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — were in an alignment that only happens once every 175 years, allowing for the possibility of low-energy travel to those planets by the Voyagers. Eventually, scientists hoped that the twin probes would be able to explore the outer reaches of the solar system.

However, there was another part of the Voyager project that was even more optimistic than the hope of exploring interstellar space. A committee chaired by the famous astronomer and science communicator Carl Sagan put together a special golden phonograph record that was affixed to each of the Voyager probes. This record, it was hoped, could be interpreted by intelligent life elsewhere in the universe — should any intelligent life actually exist and happen upon it.

Encoded in its grooves, the Golden Record contains images, sounds, greetings and — most famously — 90 minutes of music deemed representative of human life on Earth. The music includes everything from Bach to Senegalese drums to Peruvian panpipes to “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry. It’s like a mixtape for the extraterrestrial lifeforms we hope, someday, to finally meet; it’s the ultimate time capsule.

Sagan and the other scientists working on the Voyager mission were aware that the likelihood of this record being found — and understood — by extraterrestrial life was nearly zero, but they put together the Golden Record anyway. I love the optimism of that. The Golden Record, most wonderfully, contains on its surface pictorial instructions about the origins of the spacecraft and about how to play a phonograph record. The act of sending out this record is an example of humanity at its best — reaching out to the unknown with both benevolence and hope.

Images From Voyager & the “Pale Blue Dot”

Voyager 2 was actually the first of the probes to be launched. It set off on August 20, 1977, and was set to complete fly-bys of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune on its way out of the solar system. Voyager 1 was launched on September 5, 1977, and was set to complete a fly-by of Titan, one of Saturn’s moons. From there, it would continue on beyond the limits of the solar system.

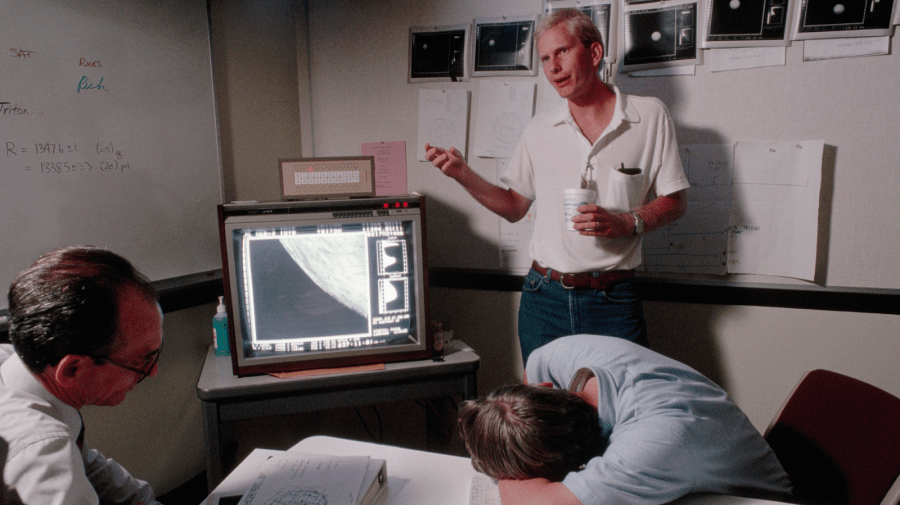

Through the Deep Space Network (DSN), the Voyagers were able to send back pictures and other data gathered during their journeys. While the photos of the planets are amazing images that have led to a much deeper understanding of our solar system, the most famous image is called “Family Portrait of the Solar System” — a composite of 60 images Voyager 1 took in 1990 before the programmers permanently shut off its camera to conserve energy.

This image became known as the “Pale Blue Dot,” the name Carl Sagan gave to the tiny speck of light in the image that represents Earth. That image was incredibly powerful; it was the first time humanity had ever been able to look at our planet from so far away. Even now, it’s a reminder that we’re all connected, both here on our tiny planet and in the midst of a huge solar system in an infinite universe.

Other Voyager Milestones Over the Years

After the cameras turned off, the Voyagers continued into deeper space, far past the last planetary bodies in our solar system. In February of 1998, over two decades after it was launched, Voyager 1 had moved farther from Earth than Pioneer 10, making it the farthest object from Earth in space.

In December of 2004 (Voyager 1) and August of 2007 (Voyager 2), the Voyagers crossed the termination shock, which is basically the beginning of the ending of our sun’s influence in space. Then, in 2012 (Voyager 1) and 2018 (Voyager 2), they went even further, crossing the heliopause — the end of the influence of our sun — and finally reaching interstellar space.

A few years ago, before the pandemic, we were all getting wrapped up in Mars Rover fever and saying goodbye and goodnight to that sweet robot in space. I found myself thinking about the Voyagers then, too. They’re way out there, quietly winding their way through the cosmos, carrying with them data we imagined, once upon a time, might signify the best we had to offer. They’re still pinging back data dutifully, too — teaching us about the universe and making us realize how little we actually know.

Where Are They Now?

Sometimes, years go by and we don’t hear much about the Voyagers. When I was a kid, I did my big seventh grade history project on the Voyager mission. I remember writing a letter to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL), asking if they might be able to send me some pictures and information in the mail. They did. That was over 20 years ago, and even then it felt like the Voyagers had already been gone for a lifetime.

Recently though, Voyager popped back up in the news cycle. It turns out Voyager 1 is sending back data that doesn’t quite make sense. In fact, while NASA says that the antenna that sends back data to Earth is still working, “the data may appear to be randomly generated, or does not reflect any possible state the [system] could be in.”

It’s not easy for NASA to communicate with the Voyagers. Voyager 1 is so far away at this point — 14.5 billion miles! — that it takes two full days for a single message to get sent back and forth. However, there have been some surprising solutions. For example, back in 2017, when Voyager 1’s primary thrusters became degraded, the engineers managed to switch to backup thrusters that hadn’t been used in 37 years. Miraculously, the backups worked.

In the end though, the power on Voyagers 1 and 2 won’t last forever. The engineers are still working on finding ways of keeping the Voyagers transmitting beyond 2025. At this stage, all of the scientific functions on board are still working. Someday though, the Voyagers will stop transmitting. But even then, the Golden Records ensure that the Voyagers always lend us the same optimism we sent them out with all those years ago. Will intelligent life ever find them? It’ll probably never happen, but one thing the Voyagers have taught me is we just never know.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman