Signed into law on April 11, 1968 by President Lyndon B. Johnson, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 is a landmark piece of legislation. A follow-up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VIII of the law is commonly referred to as the Fair Housing Act. In essence, the protections codified within the Fair Housing Act are meant to protect Americans from discrimination in housing — something that wasn’t fully realized, at the federal level, back in 1866.

Frustratingly, the Fair Housing Act hasn’t ended housing discrimination in the United States. Even today, there’s much work to be done. So, let’s take a closer look at the Fair Housing Act’s origins, the law’s intent, and why it hasn’t done enough to protect Americans from rampant discrimination.

What Is the Fair Housing Act?

Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 is often referred to as the Fair Housing Act of 1968, and was signed into law by President Johnson in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. As the Holy Week Uprising — often referred to as the King assassination riots — saw huge numbers of Americans taking to the streets, President Johnson beseeched Congress to pass fair housing laws — in addition to hate crime laws and other efforts that would fight various forms of systemic discrimination.

“President Johnson viewed the Act as a fitting memorial to the man’s life work,” the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) notes, “and wished to have the Act passed prior to Dr. King’s funeral in Atlanta.” But it wasn’t just the assassination of Dr. King that pushed lawmakers to protect Americans’ housing rights.

At the time, young, lower-class soldiers fighting for the U.S. military in Vietnam were dying at alarming rates. In particular, Black and Hispanic infantrymen were most impacted by this, and, as HUD points out, at home those same young men’s families couldn’t purchase or rent homes in the face of ongoing discrimination and racism. From the NAACP to the GI Forum, many organizations took up the cause, urging Congress to address this blatant inequity.

Efforts to pass the legislation were successful and, several days after the assassination of Dr. King, the Fair Housing Act was enacted, protecting people “from discrimination when they are renting or buying a home, getting a mortgage, seeking housing assistance, or engaging in other housing-related activities.”

Later on, discrimination on the basis of sex was added in 1974, while disabled people and families with children were added to the list of protected classes in 1988. As of now, the Fair Housing Act prohibits discrimination in housing because of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, and disability. While a 2020 Supreme Court ruling affirmed that discrimination on the basis of “sex” includes discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, HUD didn’t implement that ruling until President Joe Biden took office in 2021.

Moreover, the Equality Act, which would amend the Fair Housing Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, aims to provide consistent anti-discrimination protections for LGBTQ+ Americans in areas like housing, employment, education, federally funded programs, credit, public spaces, healthcare and more.

The Impact of Redlining and Residential Segregation

As mentioned above, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was enacted during a turbulent time, from the Civil Rights Movement to the Vietnam War to police raids of queer spaces. Housing discrimination — which became increasingly prominent in the Jim Crow era — has been ingrained in the country’s fabric.

“Real estate was to the twentieth-century what slavery was to the nineteenth,” Nathan Connolly, associate professor of history at Johns Hopkins University and author, told AAIHS. “It undergirded national prosperity. It was held in place by an elaborate web of state or state-sanctioned violence. And it required the deliberate dehumanization of a whole swath of the country on the basis of perceived racial difference.”

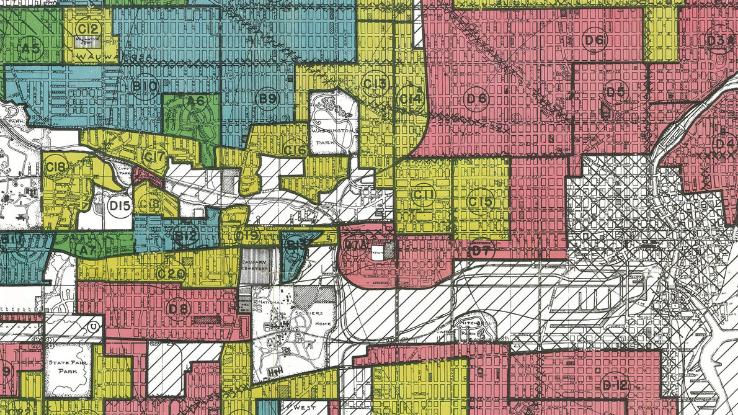

A notable form of segregation was the racist practice of redlining. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) created what they dubbed “residential security” maps of major U.S. cities. “These maps document how loan officers, appraisers and real estate professionals evaluated mortgage lending risk during the era immediately before the surge of suburbanization in the 1950s,” Bruce Mitchell PhD., senior research analyst at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), writes. “Neighborhoods considered high risk or ‘Hazardous’ were often ‘redlined’ by lending institutions, denying them access to capital investment which could improve the housing and economic opportunity of residents.”

By systematically devaluing these houses, two homes with the same characteristics in different neighborhoods — one predominantly white, and one predominantly Black — would receive drastically different appraisals based on location. Not only does this have an immediate impact, but it also has long-term, far-reaching effects. For example, homes in areas where half the population is composed of people of color are appraised for half as much as comparable homes in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Housing Discrimination and Redlining Are Not “Relics of History”

Beyond ending discriminatory housing practices, the Fair Housing Act also aimed to end segregation. People tend to work, shop, and play in the area they live. The school districts, swimming pools, and hospitals a person uses are all connected to where they reside, for example. Although segregation in public schools was outlawed in 1954, neighborhoods continue to be segregated by both race and class.

“[Black] families that were prohibited from buying homes in the suburbs in the 1940s and ’50s and even into the ’60s, by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), gained none of the equity appreciation that whites gained,” author Richard Rothstein explains on NPR’s Fresh Air. Rothstein goes on to point out that housing programs that began under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal were part of a “state-sponsored system of segregation.” Think of Long Island New York’s Levittown, an FHA-sanctioned segregated community that billed itself as America’s first suburb.

Even now, the real estate industry has found ways to discriminate in the face of the law. In 2019, Newsday reported that Long Island-based real estate agents continue to steer white home buyers toward white, more affluent neighborhoods and people of color toward low-income neighborhoods.

“The myth of the Black criminal was used to justify many Jim Crow laws. Now that Jim Crow has ended, that rhetoric continues to drive mass incarceration and its deleterious impact on Black people and Black communities. Crime-free ordinances fit squarely into this history,” Deborah Archer, associate professor of clinical law at NYU Law, explains in a conversation with New York University. “They have the purported goal of stemming crime in rental housing, but the truth is that they are more effective at excluding racial minorities and promoting racial segregation.”

Although federal agencies spend millions of dollars on testers who attempt to find Fair Housing violations, most reports are filed by those who have been discriminated against. Unfortunately, however, the Fair Housing complaint system isn’t incredibly accessible, and, in some cases, renters and homeowners don’t know they are experiencing discrimination. For example, landlords with no-pet policies are discriminating against folks with service animals, but this kind of policy has been so normalized that renters may not think to address it.

“Housing discrimination is often perceived as a relic of history, and of course that is not true,” Archer tells NYU. “People also frequently believe that lingering segregation is driven by regrettable, but understandable private choices beyond the reach of the law — rational decisions motivated by the desire to live in safe communities with high-quality schools, good amenities, and high property values. They do not see the ways that laws and public policy drive residential segregation.”

While the Fair Housing Act has helped some Americans, it clearly hasn’t done enough to implement fair, equitable practices that benefit all Americans. That is, corrective action is needed to end housing discrimination, residential segregation and the other issues that plague both renting and home-buying.