Since the early hours of February 24 marked the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and Europe’s first major war in decades, the world has watched as explosions have reverberated across Ukraine’s capital and, eventually, other highly populated cities. In just over a month, the war in Ukraine saw over 5 million refugees flee to other countries and another 7 million become internally displaced within Ukrainian borders. Between February 24 and May 3, 3,193 civilians were killed and another 3,353 were injured.

Beyond efforts to end the war focusing on saving lives and preventing further direct humanitarian devastation, another silent victim of the country’s crushing new reality could continue harming Ukrainian communities long after the last Russian troops have left: the natural environment.

With every missile explosion, raging fire and building collapse, high concentrations of pollutants are being released to permeate the country’s water supply, soil and atmosphere. Apart from the environmental consequences of harmful heavy metals, fine particulate matter and toxic gas, experts affirm that these pollutants can also raise the risk of cancers, developmental disorders and cardiovascular disease in people.

Ecoaction, a Ukrainian environmental advocacy group, recorded almost 150 environmental crimes committed by Russia in the first 47 days of the invasion. “Crimes against the environment are not only about nature, it’s about people,” said Ecoaction’s head of environmental crimes Yevhenia Zasyadko in a press release. “This war can cause many deaths in the future due to polluted water. We record soil pollution and mining of our fields. Food security and our fertile soils are in great danger caused by the actions of the occupiers.”

History Can Tell Us How War Affects the Environment

Possibly the most infamous example of war’s negative impact on the environment happened during the Vietnam War, when U.S. forces covered 4.5 million acres of rainforest and wetlands with “tactical” herbicides, including one known as Agent Orange. These highly toxic dioxins — persistent organic pollutants that break down in the natural environment very slowly — continue to contaminate soil, water, aquatic species and the local food supply in Vietnam more than 50 years later.

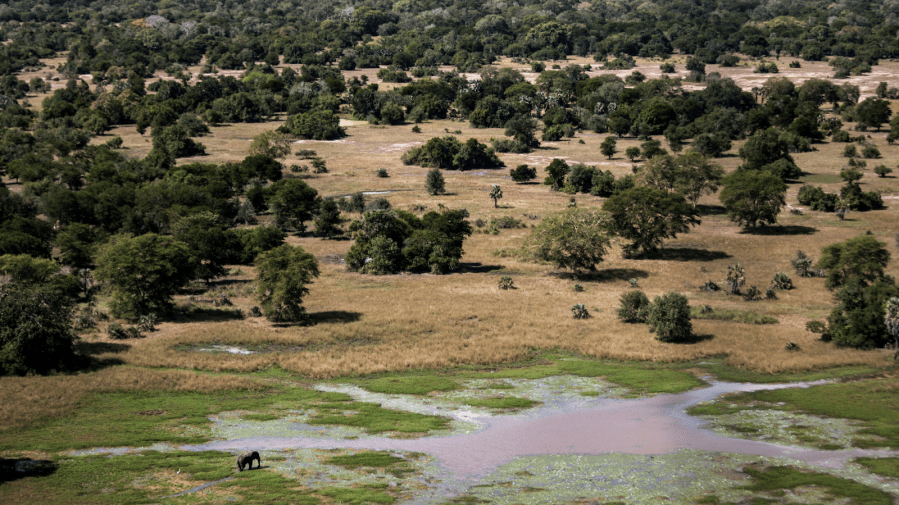

Research on past conflicts suggests that wars can lead to significant losses in biodiversity and impede conservation activities to cause irreversible environmental damage. According to a 2018 study, armed conflict is directly correlated with declines in wildlife across even protected parts of Africa. In Mozambique, where civil war from 1977 to 1992 destroyed 90% of Gorongosa National Park’s wild elephant population as both sides poached ivory to finance the war, the species actually evolved to lose their tusks as it gave them a higher chance of survival. In addition to their cultural significance, African elephants play a crucial role in maintaining plant populations and balancing natural ecosystems within their range.

Environmental stressors caused by war, such as land degradation, pollution, floods and lack of access to clean water, can exacerbate tensions and lead to further conflict and competition over precious resources — in fact, studies show that conflicts over water within countries and between countries are already increasing worldwide. Likewise, wars typically result in food shortages and economic insecurity, often driving both civilians and armed forces to rely on natural resources, sensitive habitats and vulnerable wildlife.

Widespread Pollution

Ukraine is a huge agricultural country with the potential to feed a large portion of the world. Of the country’s total land area of 60 million hectares, about 42 million are classified as agricultural land. The missiles, bombs and tanks that Russia brought onto Ukrainian soil are all filled with waste, delivering polluting contaminants to land normally used for agricultural purposes. These pollutants don’t just affect crop production now, but will hinder future generations once it comes time to rebuild.

Apart from what Russia is bringing into Ukraine, it’s also necessary to consider the chemical plants, factory storage facilities, oil deposits, coal mines and gas lines that were already there. These industrial sites can release formidable levels of pollution if they’re damaged. Similarly, the fires formed from missile strikes and other destructive activities have consequences that include air contamination and water runoff contamination.

When Russia seized Chernobyl, the now-abandoned site of the worst nuclear disaster in world history, scientists and civilians alike waited with bated breath as soldiers dug trenches in the highly radioactive soil, flew jets over restricted airspace and took workers hostage at gunpoint. Damage to these nuclear waste storage facilities could produce sizable radioactive contamination, locally and far beyond the site’s borders. Russia’s invasion also marked the first time in history that a nation’s war strategy included occupying a nuclear plant, painting a grim picture of a future where every nuclear plant could be used as a pre-installed nuclear bomb.

Threats to Biodiversity and Habitats

The Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, one of the largest nature reserves in the country, lies on the southern coast of Ukraine. A protected sanctuary for migrating birds and vulnerable species, over 700 types of flowering plants and 3,000 species of invertebrate animals take refuge in its 220,000 acres’ worth of coastal waters and wetlands.

The territory of this UNESCO-designated reserve, now occupied by Russian troops, has already suffered massive fires due to fighting near the city of Kherson. It still isn’t clear how much of the habitats there have been destroyed by active battles and the weight of military vehicles encroaching over the landscape, but the initial fires were large enough to be detected from space.

Increasing Deforestation Pressure

Ukraine is usually the world’s biggest producer of sunflower oil, historically generating one-third of the world’s supply and accounting for almost half of global exports. Sunflower oil has long been used in a wide range of food products as a replacement for palm oil, a major driver of deforestation in places like the Amazon rainforest. As the war causes exports to tank, some desperate companies are considering going back to palm oil to maintain production.

The invasion has also presented timber supply chain challenges for construction (Russia is the largest exporter of lumber and seventh biggest exporter of forest products worldwide), putting additional pressure on the illegal logging industry elsewhere. The Forest Stewardship Council, which provides the world’s leading certification process for sustainably sourced wood products, has also suspended all trading certificates in Russia.

According to Ukraine’s Ministry of Energy and Environment Protection, over 1,500 Russian missiles had been launched at the country as of mid-April. Entire cities have been destroyed and others have been severely damaged. Once the Ukrainian people begin to restore infrastructure post-war, most (if not all) of the construction materials will be sourced from the country itself. A potential increase in wood, stone and other resource extraction could take an even further toll on the already-damaged natural environment.

What the War Means for the Future of Environmental Research

It’s no secret that war uses up a tremendous amount of energy. Moving troops and heavy equipment, planes and missiles — all take up oil and fuel that emit greenhouse gasses as they burn. Already, the war in Ukraine has risen global oil prices to historic levels, which in turn drives up costs for consumer products like food, fertilizer and electronics.

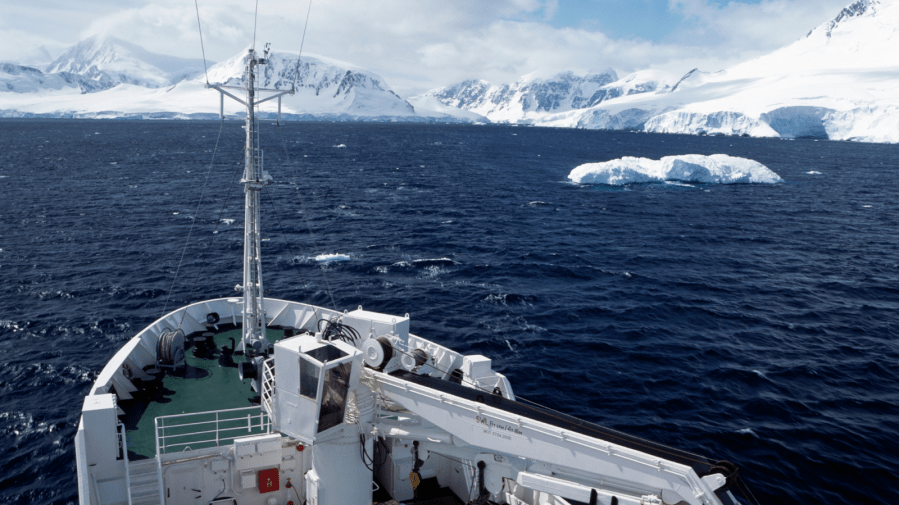

As countries around the world reduce dependency on Russian imports, international collaborations between climate scientists are also feeling the tension. Russia controls a substantial portion of the Arctic coastline and ocean territory, where some of the world’s most crucial research on carbon emissions also takes place. Now, this research has come to a detrimental pause as scientists stop any scientific association with Russian researchers.

Russian scientists were also banned from the Arctic Science Summit Week in Norway, an Arctic-research meeting hosted by the International Arctic Science Committee, responsible for coordinating international research in the Arctic. Organizers for the event, Jørgen Berge and Geir Gotaas, told The Wall Street Journal that, while they knew barring researchers from Russian organizations would complicate research efforts, they felt that they needed to take action in light of the conflict. “We are—as ever—strong supporters of scientific collaboration, but in the current situation the scientific benefits of maintaining official links with Russian institutions are outweighed by the need to take a clear stand against the actions of the Russian government,” they said.

Just before the initial attacks, a global consortium of permafrost scientists was preparing to embark on a multi-year, Arctic-wide monitoring effort that would have provided vital data on how the region is warming. Sue Natali, Arctic program director for the Woodwell Climate Research Center, told TIME magazine that at least half of their work would have taken place in the Russian portion of the Arctic. As the region is also warming four times faster than the rest of the world, that data is nothing short of essential. “We cannot just ignore what is happening with permafrost in Russia,” she said. “It’s a massive blind spot.”

Scientists who study permafrost (rock or soil that has remained frozen for at least two years) in the Arctic do so in order to learn more about the past climate and how frozen earth changes — and may continue to change — over time. It’s difficult to say how the lack of shared data between Russian researchers and the rest of the scientific community will impact the future of climate research, but it certainly has the potential to set it back.

Katherine Gallagher

Katherine Gallagher