Recently, NASA began releasing images made by its most advanced telescope ever. The James Webb Space Telescope, which is operated out of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, is the result of an international collaboration between NASA and space agencies in Europe and Canada. It uses infrared technology to observe and record the universe around us.

And the images the Webb Telescope is capable of creating are amazing. When the first images were released, people were blown away. Scientists involved with the project went on record that the telescope is working even better than they expected.

What all of this means is that we now have images of things we’ve never quite seen before. Space exploration, in the scope of human activity, is both ancient and brand new. Humans have always observed the heavenly bodies in the sky above, but the ability to do so with so much clarity and at such great distances seems to be increasing dramatically. It’s exciting, and it’s a little overwhelming.

It also has the capacity to change how we think about the world, the universe and our place within them both. Over the past 75 years, advances in imaging technology have shown us things that help us think differently. Each advance in our capacity for seeing opens up the possibility of new ways of understanding. Let’s look at some of the most significant images that have been made (so far!) of outer space.

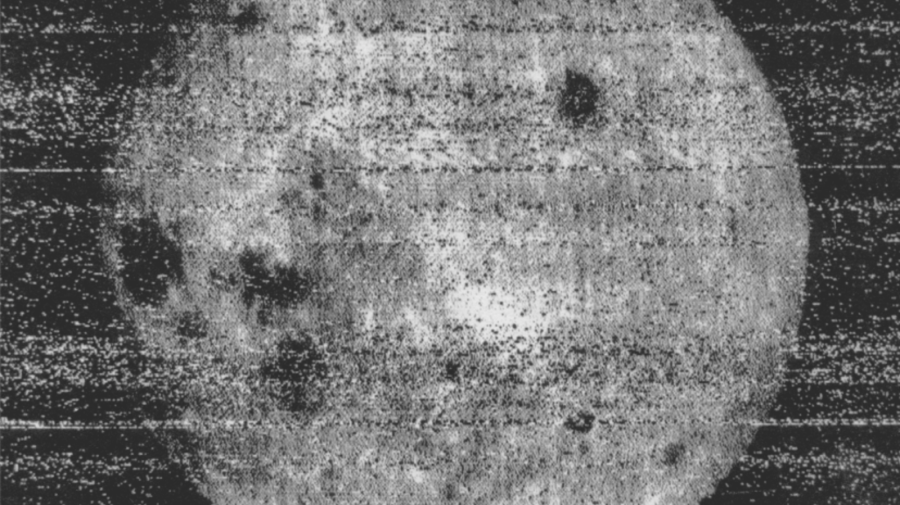

The Far Side of the Moon (1959)

One of the most important early images was this crude image of the far side of the Moon. Difficult as it is to discern compared to more contemporary images, the image was profoundly exciting to see in 1959. The 29 photos taken by the Soviet spacecraft Luna 3 were processed by the onboard processing unit and sent back to Earth via radio transmission.

For those of us young enough to not recall a world without pictures of bodies in outer space, maybe it’s tough to really feel how amazing it would have been to see an image like this at the time. This first image of something that was quite literally impossible to see from Earth radically changed how people imagined the possibilities of space observation moving forward.

Earthrise (1968)

Here on Earth, images of sunrise and sunset are timeless for their beauty and for their symbolic value. Scroll through your Instagram feed and I’m sure you’ll see a few without having to try too hard. This famous image taken from Apollo 8 in 1968 flips the traditional sunrise shot around, giving us a view that centers the physical beauty of our home planet. It was immediately an important image, and sparked a movement toward environmentalism with the perspective it provided. It reminded human beings that Earth itself is special.

It also became a famous cultural touchstone. There was a postage stamp with the image on it in the U.S. as early as 1969. Joni Mitchell’s 1976 song “Refuge of the Road” mentions “a photograph of the Earth taken coming back from the Moon.” In short, it’s one of the most famous images of all time, period.

Walking on the Moon (1969)

You can’t talk about important images of outer space without discussing the first photographs of people walking on the surface of the Moon. Apollo 11’s Lunar Module’s landing on the surface of the Moon is such a famous moment in history that it’s picked up a great deal of mystery over the years. Rumors of the Moon landing being faked have persisted ever since the event.

It might be the case that the mystery is enhanced by the surreal quality of the images themselves. The futuristic shimmer of the space suits, the bizarre and haunting light that’s unlike anything here on Earth — these factors can make you feel like you’re looking at something out of a dream when you see these pictures. Nevertheless, the ability to watch one of us walk on the Moon certainly was a watershed moment in the history of our feelings about outer space.

The Blue Marble (1972)

If “Earthrise” was a seminal moment in showing human beings the beauty of our home planet, “The Blue Marble” was the next step in that journey. Taken by astronaut Harrison Schmitt aboard Apollo 17, the photo was yet another bit of fuel that fed the fire of environmentalism in the 1970s.

Interestingly, Apollo 17 was the last manned flight to the Moon, and so it’s also the last time that a human being was far enough away from Earth to snap a photograph like this one. There’s something special about that, even as telescopes like Webb now show us pieces of the universe that we were almost unable to imagine back in 1972.

The Great Red Spot (1979)

Seeing Earth in pictures like “Earthrise” and “The Blue Marble” heralded a cosmic shift for human beings, forever changing the way we imagined our own planet. But the probes Voyagers 1 and 2 provided the ability to feel that way about more distant parts of our cosmic neighborhood. The Voyagers traveled through the outer reaches of our solar system (and are still traveling into interstellar space even now).

Through the images the Voyager probes sent back, we were able to see the beauty of parts of the solar system we’d only seen as distant points of light up until then. Perhaps the most famous of these images is this one of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, taken by Voyager 1 in 1979. The gigantic, swirling storm — itself larger than our entire planet — looks like something out of an impressionist painting. The sheer size and beauty of it boggles the mind and can’t help but expand our view of our little corner of the universe.

Pale Blue Dot (1990)

“The Blue Marble” showed people how gorgeous Earth looked from space, and inspired many people to protect it. But the “Pale Blue Dot”, an image of Earth taken from billions of miles away from the sun in 1990, inspired a different reaction. It was part of the last series of images Voyager 1 took before shutting off its cameras to conserve power. The images were compiled into what became known as the “Solar System Family Portrait”.

As a child, I remember seeing a video in which the famous astronomer Carl Sagan explained the power of the image, reminding us that this little speck of light in all of that vastness of space contained on it “everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of.” If “The Blue Marble” reminded us of how important Earth is, “Pale Blue Dot” reminded us of just how small we are.

The Horsehead Nebula and The Hubble Telescope (2013)

The Hubble Telescope itself was yet another important development in our ability to observe our universe. The advent of a telescope that could, itself, be launched into space had been imagined as early as the 1920s, but it wasn’t until 1990 that Hubble launched.

There have been many, many incredible images taken by Hubble over the years. This one of the Horsehead Nebula — a dark cloud of dust and gas — was first photographed in 2001 after NASA polled people about what they wanted to see most. This version was updated in 2013 as part of the 23rd anniversary of the telescope’s launch.

Pluto Up Close (2015)

For many years, Pluto held the special distinction of being the most distant planet in our solar system. However, you might remember that sometime around the year 2000, there was an ongoing debate about whether Pluto was, in fact, a full-blown planet at all. Whether it is or isn’t is a subject still somewhat up for debate, but, either way, Pluto exists.

It’s part of the Kuiper Belt, a ring of icy objects orbiting our sun just beyond Neptune. And for all of the incredible images of the outer planets sent to Earth by the Voyager probes prior to 1990, Pluto was left without its own close-up until 2015. That’s when the New Horizons probe completed the very first fly-by of Pluto, snapping some great pictures, including the one above.

The James Webb Space Telescope and Cosmic Cliffs (2022)

One of the first series of images released from the brand-new James Webb Space Telescope was this one of the so-called “Cosmic Cliffs” in the Carina Nebula. I don’t know about you, but I can’t stop looking at it. The unimaginable beauty of it is hard to wrap my mind around. Actually, it’s hard to say what’s so beautiful about it. There’s the aesthetically pleasing combination of light and color and texture, of course, but it’s something more.

Maybe it’s the idea of putting a frame around something so vast and impossible. Over the course of just my lifetime, our ability to observe the universe has come so far. Here on Earth, to be sure, we do a lot of fumbling around and messing up, but I find some comfort in the simple act of observation. It might seem silly to spend so much effort observing parts of the universe we’ll never travel to, but I find it strangely optimistic. We’re paying attention for the sake of paying attention. When you do that, you never know what you might find.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman