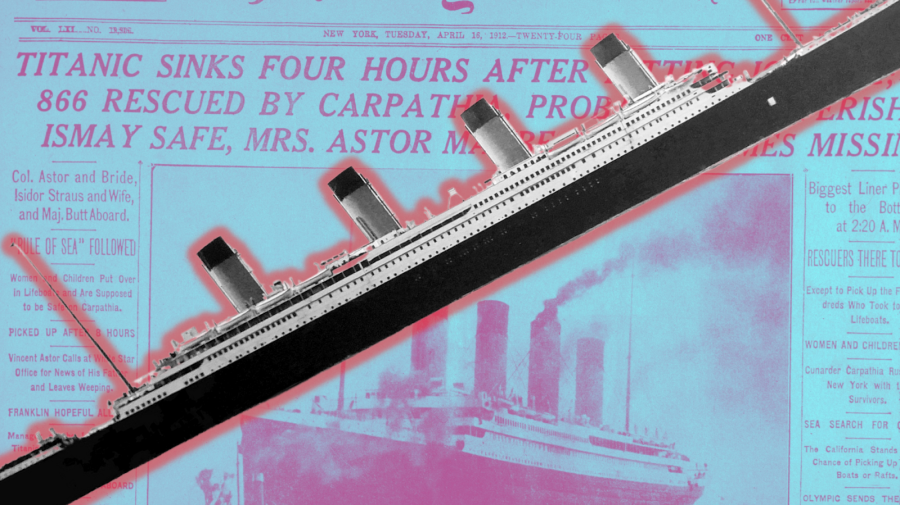

The sinking of The RMS Titanic is, without a doubt, one of the defining events of the 20th century. Almost immediately, the story captured the attention of people around the world. It’s a story of hubris (“The boat is unsinkable,” said Philip Franklin, vice president of White Star Line in 1912), but it’s also a story of sacrifice and heroism (Major Archibald Butt, for example, and countless others died helping others survive).

Songs have been a major part of the cultural experience and remembrance of the Titanic. The tragedy has been immortalized in song numerous times over the 110 years since the ship’s sinking. From Leadbelly’s “The Titanic,” to Blind Willie Johnson’s “God Moves on the Water,” to Bob Dylan’s much more contemporary “Tempest,” the famous sunken ship is an irresistible subject.

There are other musical associations: Celine Dion’s megahit, “My Heart Will Go On,” from the soundtrack to James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster, Titanic, and the hymn, “Nearer My God to Thee,” which was famously the alleged last song played by the band on the ship itself. But the song that is perhaps most closely associated with the tragic event is a tune that’s thought to have been written by William and Versey Smith, a husband and wife religious blues duo from either Texas or The Carolinas. Called “When That Great Ship Went Down,” it’s been covered and performed by endless musicians and summer camp attendees over the past century or so — but why?

Attitudes About the Sinking Ship

There was, of course, a great deal of mourning following the news that the “unsinkable” ship had, in fact, sunk. The loss of life was staggering; over 1500 people died — far more than survived. For Black Americans, there was some irony here. William and Versey Smith’s 1927 recording of “When That Great Ship Went Down” is featured in the famous 1952 Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music, and the liner notes explain that Black musicians “found it noteworthy and ironic that company policies had kept Black [people] from the doomed ship; the sinking was also attributed by some to divine retribution.”

Divine retribution or not, as Henry Louis Gates points out, statements like the one in the Washington Post from 1912 — that much of the sadness of the tragedy was due to “the character and importance of many of those who sank” — landed such that they “practically dared African Americans to insert themselves into the Titanic narrative.” In fact, there was a Black man on the Titanic, Joseph Laroche, whose story is interesting in and of itself, but that wouldn’t be widely known until much, much later.

Myth and History

In the moment, Black Americans attempted to situate themselves in the story through myth and commentary. Gates describes the popular rumors of the day, one of them that the famous boxer Jack Johnson had tried to board the Titanic but was refused entry because of the color of his skin (this myth was immortalized in the Leadbelly song mentioned above).

Ballads like Leadbelly’s and the one by William and Versey Smith were another way for Black Americans, suffering so many tragedies of their own, to comment on their absence from this particular instance of cultural mourning. During the earlier era of slavery, as Kenyatta D. Berry points out, “Music was a way for [enslaved people] to express their feelings whether it was sorrow, joy, inspiration or hope.” This tradition of expression through music is a key part of the experience of Black ballads about the Titanic, especially “When That Great Ship Went Down.”

Singing in Sadness

The idea that singing might be a way to cope with sadness should probably be no great revelation, but it can feel a little jarring when you’re singing and then realize what’s going on in the words you’re saying. The famous chorus of “When That Great Ship Went Down” goes: “It was sad when that great ship went down / It was sad when that great ship went down / Husbands and wives and little children lost their lives / It was sad when that great ship went down.”

If that feels distasteful to you, I can’t quite blame you, but I’ve always felt a kind of rush in the disconnect between the meaning of the words and the feeling of the song. To sing such devastating truth so joyously is, perhaps, a little cathartic — a way of taking back a little power in the face of a universe that can seem cruel sometimes.

I recently wrote about National Poetry Month that sometimes poetry can deliver information you didn’t know you needed. It is much the same with songs; it can be tempting to think that it’s the words themselves that contain the information, but that’s not the whole truth. How we feel is a mysterious combination of the words, the sounds, and what’s already in our hearts.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman