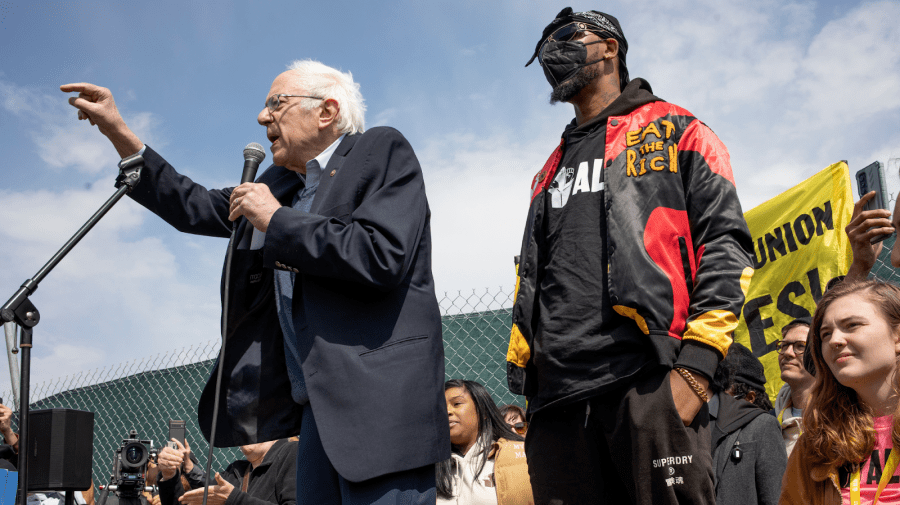

We’re all familiar with Amazon, the online-bookstore-that-could-turned-largest-online-retailer in the United States, but, as impressive as Amazon’s growth is, what’s going on behind the scenes is distressing. In early April 2022, Amazon workers employed at a warehouse, referred to as JFK8, on New York City’s Staten Island voted in the company’s first union in the U.S.

Now, as other warehouses decide whether or not to join the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) — an “independent, worker-led movement for job security, union pay, better working conditions, worker power and dignity” — it feels like there’s some hope when it comes to labor rights. Amazon, and its founder Jeff Bezos, seem to flex its seemingly infinite resources and power, but, if we learned anything from past labor struggles and present labor protests, banding together can create real change.

That said, let’s take a look at what led to this moment, and the actions both the company and its employees are taking in light of these unprecedented unionization efforts.

Amazon’s Infamously Bad Warehouse Working Conditions

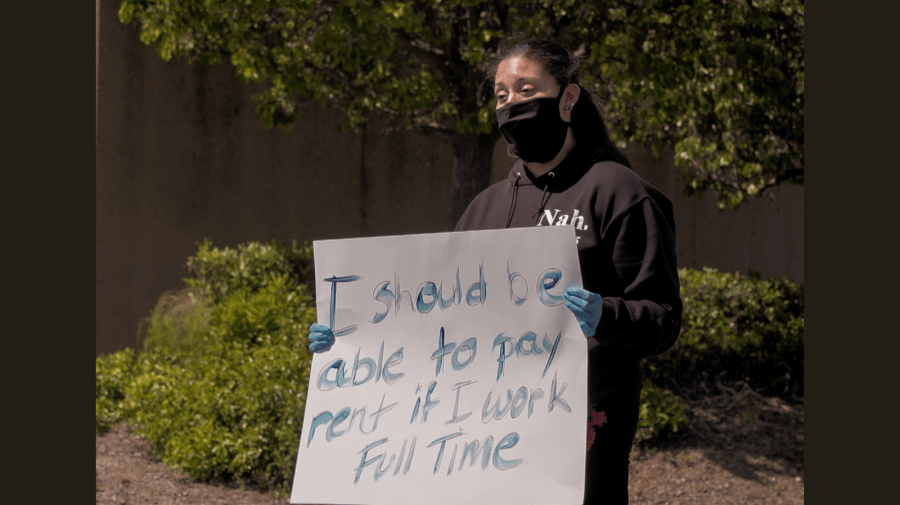

Former and current Amazon employees have reported the company’s questionable working conditions on more than one occasion. In an article published by CBS News in 2021, a former Amazon warehouse assistant manager stated that the company tracks workers every second of their day once they set foot in the building. With bathrooms being a 5–10 minute walk from many workstations, and only 15-minute breaks to contend with, simply using the restroom became a challenge.

The New York Times reported that Amazon encourages employee turnover as hourly workers no longer receive automatic raises after working there for three years; according to The Times, the company even offers bonuses to people who quit. The lack of raises reflects Bezos’ belief that long-time hourly employees are inefficient — they expect more money overtime for expending the same amount of energy, in Bezos’ view.

Bezos even went so far as to call workers “lazy” (via Insider). And with a whopping annual turnover of 150%, Amazon clearly isn’t afraid to lose (rightfully) agitated employees. In fact, even pre-pandemic, Amazon was “losing around 3% of its warehouse workers each week,” according to Marketplace, which is a huge red flag for prospective employees.

But if you treat human beings like replaceable machines, there will be consequences. Add this on top of other reports — workers being fired when payroll software marked their approved leave as them having abandoned their jobs; incorrect paychecks; and serious injuries nearly double the rate of other warehouses in the same industry — and it’s no wonder Amazon’s workers are starting to unite for better working conditions.

What Are Amazon’s Union-Busting Techniques?

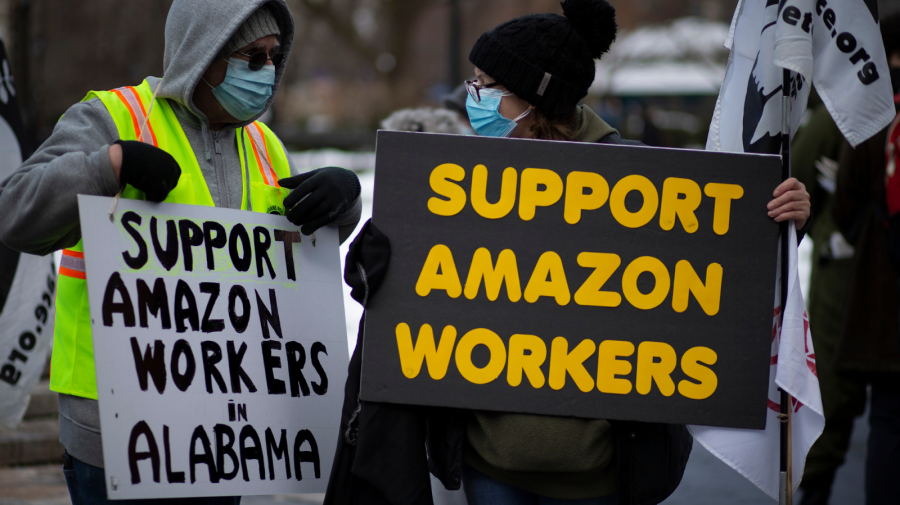

Despite the successful Staten Island vote, forming a union at Amazon is still easier said than done. Those who’ve experienced previous labor fights with Amazon say that the company will use any means necessary to prevent unions from forming.

For example, at an Amazon warehouse near Birmingham, England, workers filed documents to form a bargaining unit in 2019. In response, Amazon challenged the number of supporters who signed on and successfully prevented the union’s formation. So, when the Amazon workers at the JFK8 warehouse successfully voted to union on April 1, 2022, it really was a history-making victory.

As expected, Amazon isn’t content to let their workers organize; as of April 8, 2022, Amazon filed claims that the union vote was tainted, pushing for a redo. The company listed 25 objections and accused labor rights organizers of intimidating workers to vote in favor of the union. Amazon also stated that the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) failed to protect the neutrality and integrity of the procedures by not controlling the media presence around the voting area.

But, in actuality, Amazon itself has been trying to mess with voting results. In Bessemer, Alabama, for example, the company bombarded workers with anti-union messaging, eager to postpone the vote. When the NLRB discovered these instances of intimidation, it announced that Amazon had violated labor laws.

Intimidation isn’t the only tactic Amazon plans to use to prevent unions. Instead, it’s getting even more dystopian; the company has plans to create an internal messaging app for employees — but it will control the platform. Does that sound harmless to you? If so, think again. Reportedly, the app would ban words and phrases such as “union”, “diversity”, “restrooms”, “this is concerning”, “slave labor” and “living wage”, making it more challenging for employees to organize and voice their concerns with one another. If you have to ban terms like these, odds are you’re doing something wrong.

Additionally, Amazon already uses software, a spy agency, and predictive analytics to determine which workspaces are at a “high risk” for union activity. It seems Alexa isn’t the only one watching.

Amazon’s Alleged Commitment to Social Issues Rings Hollow

Given Amazon’s actions (and inaction) when it comes to their employees fighting for basic labor rights, it’s hard to imagine that the company really wants to support causes like housing equity and hunger relief.

In 2021, Amazon launched the Amazon Housing Equity Fund, which has since helped provide affordable long-term housing to an estimated 18,000 people through partnerships with local governments and non-profit agencies as well as the use of grants and low-rate loans. But the company also believes that no one should go without food, and has partnered with food banks and schools to provide meals for families and kids.

Despite these good deeds, Amazon isn’t actively working to change its policies and create better working conditions for employees. Yes, the company is helping people with long-term affordable housing and daily meals — and, yes, the company even supported movements such as Black Lives Matter through financial contributions — but all of this seems more like a form of damage control than a genuine dedication to helping people. In essence, these acts help distract us from the company’s pattern of creating dangerous working conditions and exploiting its employees.

Simply put, all their “good” acts don’t stem from a motivation to do better. Instead, Amazon is interested in creating a smokescreen, and building up a positive word-of-mouth image — one they hope people will remember amid the accusations of unsafe working conditions.

The History of Company Towns: Could Amazon Head Down This Path?

While they aren’t actively creating company towns, it’s hard not to see how Amazon campuses, in a way, are like their own company towns in some locations. Amazon has a sprawling network of delivery hubs, each with many people working for them. This means that the e-commerce giant attracts many people, sometimes whole communities and families. In fact, Amazon’s Seattle workplace has as much office space as the subsequent 40 largest employers combined.

Okay, but what’s meant by a company town, then? For that answer, we’ll look toward history. The company town of Pullman, located in Illinois, is one such example.

The Pullman Palace Car company manufactured luxury and sleeper rail cars; to improve efficiency, Pullman created a town for workers and their families, complete with a park and library. In 1893, Pullman implemented a pay cut for its workers, which averaged 25%, but the company didn’t lower the rent of the houses — houses Pullman owned, because well, it owned the whole town.

Sometimes, company towns housed their workers in fenced-in areas or paid employees with a currency or item that was only accepted at stores the company owned, meaning that employees worked to dump their paycheck back into the hands of their employer. While Amazon hasn’t created any official company towns per se, the company does employ communities who depend on the higher wages (wages start at $15 per hour, which is a solid starting rate in many states) to survive, only to find themselves unable to bear the concerning working conditions.

Entire communities, unemployed and looking for work, often feel an initial sense of relief when a larger company adds a warehouse full of jobs. After all, there are family expenses, bills and debt to manage. But too much control — being the only job choice in some areas — then makes it more challenging for employees to find work elsewhere if the conditions are poor. This kind of economic trap, whether intended or not, is quite similar to that of company towns of the past.

What Can Amazon Learn From Its Staten Island Workers?

Companies often oppose unions because they fear a loss of control, believing that unions will interfere with their autonomy, or that the union’s requests — like higher wages, better working conditions, solid benefits and/or longer breaks — will result in financial losses. As a result, employers often try and maintain the status quo at the expense of their workers’ rights. Unfortunately, it’s a tale as old as time.

Even though Amazon is currently fighting the results of the Staten Island vote, they might be better off considering the many benefits unions offer a company. Better working conditions and better pay actually enhance productivity — contrary to what Bezos believes — and annual raises, not just higher income, help keep employees motivated and feeling valued. In the end, companies with unions see lower employee turnover and improved workplace communication — without the need to ban words.

It’s not that people don’t want to work; they simply want the ability to thrive at home and in the workplace. The Staten Island vote shows us what organizing can do, even today. After all, labor unions were the ones to bring about the weekend, and now we all benefit from a five-day work week (though, of course, there’s always room for improvement there, too). When labor unions facilitate better working conditions and pay, those standards become the norm, and the effects spread outward, even to companies and organizations without unions — and that’s a win for all of us.