You may be a person of discerning taste, watching only the best films and television shows, and appreciating only the finest moments of pop cultural life. That’s great, but I’m here to tell you you’re missing out, dear reader. There’s a whole world of supposedly “bad” movies out there, just hanging around on the virtual shelves of the streaming service universe, waiting for you to watch them with the kind of joy that’s unencumbered by the need to be considered fine art.

Many of these so-called “bad” movies — and, for the purposes of this exercise, we’re going to define “bad” as movies with a score of 60 or lower on Metacritic — are genre movies, meaning they’re movies made with the goal of fitting into a specific genre. Think rom-coms, sci-fi movies, horror movies, and so on. One of my favorite genre categories is the disaster movie, and if you want to drill down even further than that (and, for the record, gigantic outer-space drills will 100% be appearing on this list), what I really love is the natural disaster movie.

What Is a Natural Disaster Movie, and What’s a Recent Example?

In a natural disaster movie, some part of planet Earth is threatened by a natural force, be it a volcano, earthquake, flood, or Texas-sized asteroid. Natural disaster movies ask us to think about the global forces at work around us; specifically, they ask us to think about what happens if these forces try to kill us. That can be scary, which is why bad natural disaster movies are so important. The unintentional humor, the absurd special effects, the ludicrous dialogue: this stuff all serves to help us take everything a little less seriously. Sure, maybe we’re doomed, but can’t we at least have a little fun in the meantime?

The most recent entry into the bad natural disaster movie canon is Moonfall, which will be available digitally on 4/1 and is rocking out with a score of 41 on Metacritic. Directed by master of the genre Roland Emmerich (don’t worry, we’re not done with him), Moonfall is about the Moon…falling. That’s exactly as bad for us here on Earth as you’d think. This review built purely out of quotes from Moonfall sums it up pretty well. Not a masterpiece, but a pretty fun way to spend a couple of hours, and that’s exactly what we’re going for here.

Dante’s Peak and Volcano: The 25th Anniversary of a Double Disaster

Perhaps the peak (pun intended) of the bad natural disaster movie genre came in the spring of 1997, when Hollywood, for some reason, decided to bestow upon us not one but two totally ridiculous movies about volcanoes suddenly destroying the surrounding landscape: Dante’s Peak (Metacritic score: 43) and Volcano (Metacritic score: 55).

There are two kinds of fantasies at work in these films. One is a fantasy of hyper-vigilance: we want to believe that if we paid just enough attention, we could see the disaster coming, right before it’s too late. The volcanologist at the center of Dante’s Peak (Pierce Brosnan) and the L.A. Office of Emergency Management Director in Volcano (Tommy Lee Jones) are both told by the people around them that they are being too vigilant, too worried, too paranoid. Of course, the fantasy here is the fantasy of being right.

The other kind of fantasy is a fantasy of morality. All the people we are asked to identify with in these movies make difficult ethical choices in the face of grave danger. They risk it all to do what’s right. They run toward the danger, not away from it. There’s a scene in Volcano where Jones runs toward a collapsing building to save a woman and a child, and it’s exhilarating to watch. You feel caught up in it. You want to believe that you would do the same thing, and the fantasy is that you might.

The “bad” natural disaster movie is always built on fantasies like this. These movies let us have a little fun while playing the game of thinking about what we’d do in any number of terrifying situations. Whether you’re a long-standing fan of the genre or just curious about how to dive into the world of “bad” natural disaster movies, here are some other must-watch classics from the last 25 years.

Armageddon (1998)

No list of disaster films can be complete without Armageddon (Metacritic score: 42), which improbably was at the absolute center of American culture when it came out in 1998. It was the biggest movie at the box office (it made over half a million dollars) and it featured the biggest song (Aerosmith’s “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing”). Most importantly, it had the highest stakes. The premise of Armageddon is this: NASA discovers an asteroid “the size of Texas” that’s gonna smash into Earth in 18 days, ending life as we know it.

They decide — as anyone would — to send a team of oil drillers led by the hilariously-named Harry Stamper (played by Bruce Willis) to drill a hole deep into the asteroid, insert a nuclear bomb, detonate the bomb from a safe distance, and split the asteroid, diverting its course in the process.

Simple, right? Well, it doesn’t go as planned, and we get to imagine what we would do if we were Harry Stamper, forced to (spoiler alert!) sacrifice himself to save literally all human life. This movie is ridiculous, but it has become the go-to reference for an entire generation of people when they think about the concept of their lives flashing before their eyes. Take that, film critics!

Deep Impact (1998)

You’re not going to believe this, but there was another Hollywood movie in 1998 about an outer-space object careening toward Earth. The difference between Armageddon and Deep Impact (Metacritic score: 40), however, is that Deep Impact is about emotions. You see, it’s not just about the life-snuffing comet — it’s about how this event will have a “deep impact” on our lives.

Other than that? Pretty similar to Armageddon in lots of ways. It’s a comet instead of an asteroid, sure, but we still have to send people up there with a giant drill and a bomb, and we still have to try to split that sucker in two. This time, after the split, one of the pieces is still on a collision course with Earth. I don’t know how much to worry about spoiling endings here, but one of the things that feels interesting about Deep Impact is that the day isn’t really saved.

The Core (2003)

I’m starting to think this should have been a list of movies about really huge drills. The Core (Metacritic score: 48) takes the classic formula of Armageddon and Deep Impact and turns it inside out. This time, the problem is inside (and it’s really tempting to do a whole reading about how as we learned more about climate change in the late ‘90s and early 2000s our fears shifted inward, but we need to stay focused here).

It turns out that the U.S. government is testing a secret, weaponized system called DESTINI (Deep Earth Seismic Trigger Initiative), which, coincidentally (oops!), is slowly stopping the planet’s rotation. Obviously, this means we’re going to have to drill into the molten core of the Earth and set off a nuclear blast to get things moving again.

What has always won me over with this movie is the campy, over-the-top performances of Stanley Tucci, playing the egomaniac scientist Dr. Zimsky, and Delroy Lindo as Dr. “Braz” Brazzelton, the designer of the aforementioned really huge drill). The secret weapon of any great “bad” natural disaster movie is that the supporting characters can’t just be cashing a paycheck. They need to really go for it, and Tucci and Lindo absolutely go for it here.

The Day After Tomorrow (2004)

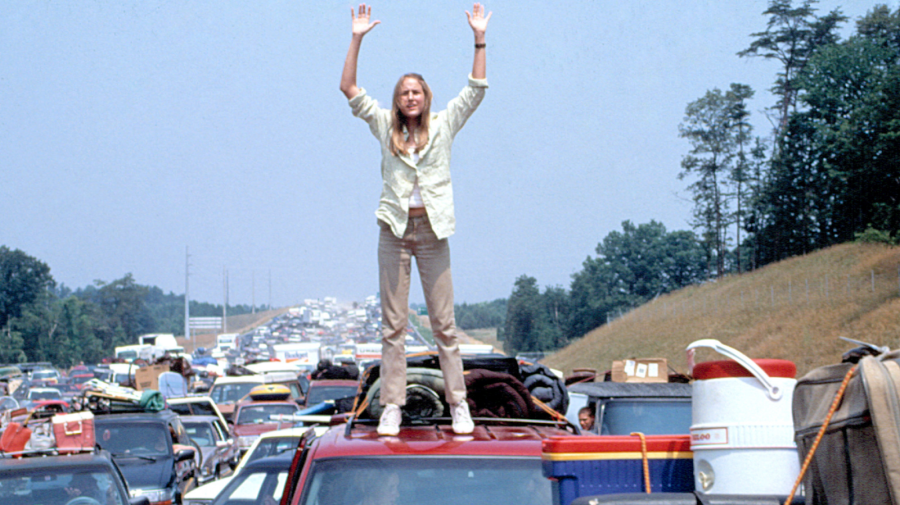

These things sure do seem to keep coming in twos. In Roland Emmerich’s The Day After Tomorrow (Metacritic score: 47) global warming is front and center, and the results are surprising. According to Dr. Jack Hall (played by Dennis Quaid) melting polar ice is changing ocean currents, and those changing currents are about to trigger an ice age! It’s a tale as old as time, though: nobody believes him until things start to go terribly wrong, and then, finally, they trust Jack.

Meanwhile, Jack’s son Sam (Jake Gyllenhall) is in New York City with a bunch of other high school students, participating in an Academic Decathlon — not to brag, but I myself was a nerdy Academic Decathlete in my younger days — and there’s another kind of natural disaster going on: Sam has a crush on his fellow decathlete Laura ( Emmy Rossum), who seems to be more into some other dude.

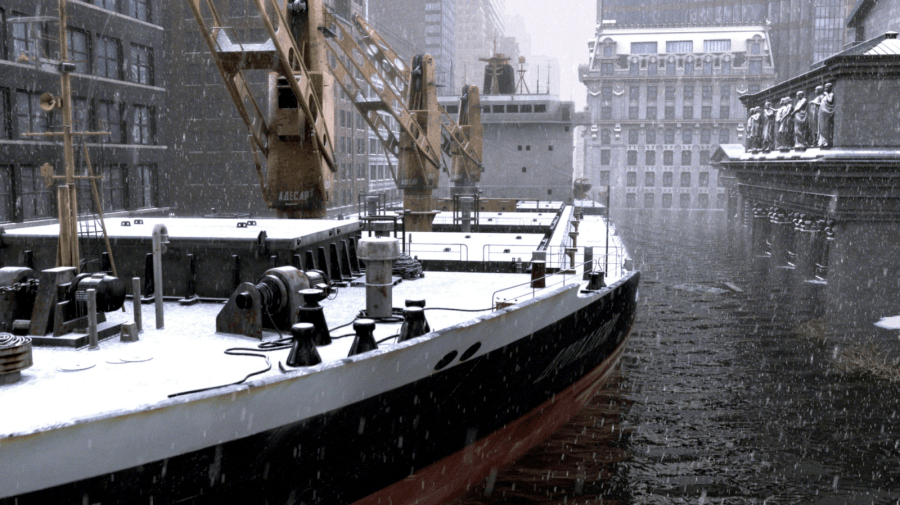

Anyway, the entire Eastern Seaboard starts freezing, so everyone has to huddle by a fireplace in the New York Public Library while Jack makes his way from Washington D.C. to New York City (mostly) on foot. There’s a lot happening here: people are burning rare books for warmth, the entire population of the United States is advised to flee to Mexico, and while frantically searching for penicillin, Sam and his friends get attacked by wolves on a Russian cargo vessel that floated into Manhattan before everything froze. You know, normal stuff. In the end, things may have changed, and many people may have died, but the remaining characters realize that we can still come together, and that’s what’s important.

San Andreas (2015)

There are lots of earthquake movies, of course, but San Andreas (Metacritic score: 43) is probably my favorite, mostly because it seems to come down to The Rock vs. an earthquake, and that’s a really fun battle.

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson plays a helicopter-rescue pilot named Ray who’s going through a divorce. That’s the small-scale, human interest piece of this movie. In the meantime, Paul Giamatti plays Dr. Hayes, a seismologist at Caltech who discovers that the entire San Andreas Fault is about to shift.

In this “bad” natural disaster movie, we keep things relatively small-scale in general. Instead of the whole world being in danger, it’s just most of the West Coast of the United States. Through the strange mechanisms of fate and the heart, Ray and his ex-wife (Carla Gugino) make their way via helicopter from L.A. to San Francisco to rescue their daughter (Alexandra Daddario).

Stick around for one of the greatest, most improbable CPR rescues of all-time (this is another topic that deserves its own list), and for The Rock squaring off against falling buildings and tidal waves.

Geostorm (2017)

We save the best (meaning, in this case, the worst) for last around here, so we’ll end with Geostorm (Metacritic score: 21). This movie holds a special place in my heart. When it came out, I was teaching high school — specifically, I was teaching an interdisciplinary class in English, Science and History. We were in the middle of a unit on climate science, and had just discussed the concept of “Geoengineering,” so it was particularly fun to see a movie drop into theaters with the premise of Geoengineering going horribly wrong.

Here’s what happens: in the near future, after a series of climate disasters, an international coalition decides to release a network of climate-controlling satellites. These satellites basically block sunlight to artificially cool the planet, but don’t worry, we’ve got this under control. Surely, the world’s governments can be trusted with this God-like power…

Geostorm features a really great bad guy performance by Ed Harris as the U.S. Secretary of State, and a really fun good guy performance by Gerard Butler as the person who designed the satellites and (later) the only one who can stop them. After all, there has to be someone with the power to stop these terrible things — for all the heroic fantasies these movies are built around, that’s the one we really wish were true.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman