Throughout history, it tends to be the case that folks have a tough time accepting change. It seems like in every era, many people can’t help but feel like things used to be better. Of course, not everyone feels this way — you can’t really argue that the past was better than the present to groups of people who have rights and privileges now that they once weren’t afforded in the past.

Looking back, it can be hard to remember that the strides American culture has made toward equality had to be fought for in the moment. And the very fact that equality has to be fought for is evidence of the fact that it was (and is) opposed. It feels important to keep that in mind when considering the cultural debates of today.

Recently, we’ve seen lots of instances of anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-trans legislation, from a Texas law preventing trans kids from participating in school sports to so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bills that would place restrictions on how educators talk to kids about sexual orientation and gender identity. The justifications for these pieces of legislation sound a lot like some of the justifications for anti-LGBTQ+ legislation from the 1960s and ‘70s in the U.S. So, let’s consider why that is, and why that comparison is so important.

The “Nostalgia Trap”

Stephanie Coontz is a scholar of history and family studies who, in 1992, published a book called The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. She argues that there are two kinds of nostalgia. One is nostalgia for, as she put it more recently, “a longing to reproduce a feeling once experienced with friends or family.” This kind of nostalgia, she writes, is really good, and tends to lead people to act “more warmly toward others, including strangers.”

On the other hand, there is a more troubling kind of nostalgia in which folks experience “the longing to reproduce an idealized piece of history.” This kind of nostalgia tends to lead people to “identify more intensely with their own group and to judge members of other groups more negatively.” It’s this second kind of nostalgia that is evoked in the language around many of the recent anti-LGBTQ+ bills being passed in states around the U.S.

It comes down to a question about whether education and discussion is the same thing as encouragement, or, worse, indoctrination. For example, the “Individual Freedom” bill that was passed by Governor Ron DeSantis in Florida has been criticized, in part, for its vagueness, because it prohibits that an individual “should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin.”

The problem is that it’s impossible to control how someone is going to feel when they learn information that makes them uncomfortable. Is it okay to teach facts that make people uncomfortable? The vagueness of the bill means that the lines between education and so-called “indoctrination” are blurred.

Anita Bryant and “The Moral Atmosphere”

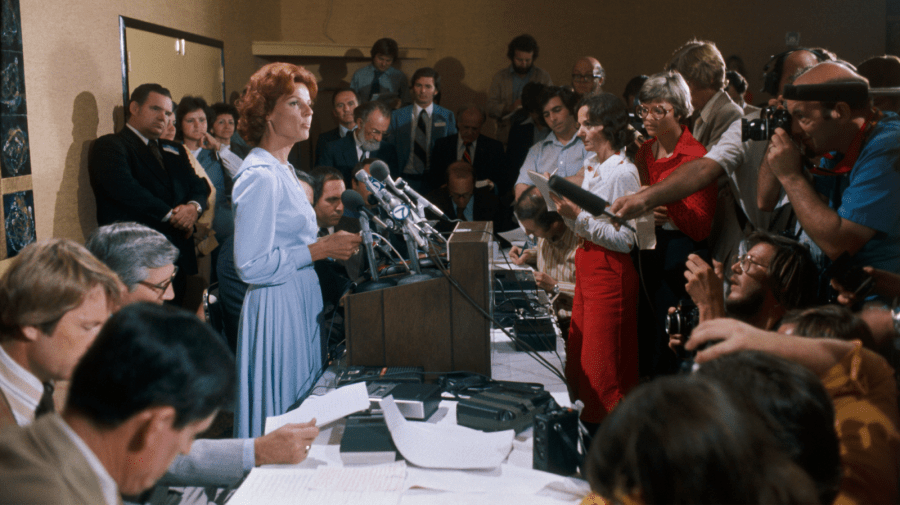

Back in the 1970s in Florida, a similar conversation was happening around the idea of whether state protections of civil rights for gay people might be infringing on the rights of parents. In 1977, Florida passed a bill that banned discrimination based on sexuality in housing and employment. Subsequently, a woman named Anita Bryant — a singer and former Miss Oklahoma — formed a group called Save Our Children and managed to get the law overturned.

She did so using pretty inflammatory language that sounds a lot like the language of these debates today. Bryant said that it was her right, as a parent, to control “the moral atmosphere in which my children grow up.” Her feeling was that equal rights for gay people to work as educators infringed on her right as a parent to control what her children learn and who they learn it from. Save Our Children’s statement that “Homosexuals cannot reproduce, so they must recruit,” was an articulation of a similarly inflamatory idea that the mere existence of people with different sexual orientations constituted an attempt infringe on someone else’s rights.

Elsewhere in the 1970s, as bipartisan momentum gathered nationwide for the passing of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), folks mobilized against that as well. Phyllis Schlafly and the Eagle Forum argued that the ERA would actually be bad for women — that it would infringe on their “traditional” rights. Schlafly said, “What I am defending is the real rights of women… A woman should have the right to be in the home as a wife and mother.” Both of these arguments make use of the idea that expanding equality to more people might negatively impact the freedom of people who are happy with the status quo.

What’s Happening Now?

It’s so important to pay attention to the arguments of the past, because it allows us to see more clearly the arguments of the present. And in the present, anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, as we said above, is proliferating. As of March of this year, almost 240 bills had already been filed across the U.S., most of them targeting trans people.

Similarly to the anti-LGBTQ+ movements of the ‘70s, these bills seem to constitute an attempt to hold onto the traditional views of the past without considering the fact that the traditional views of the past may have left many marginalized groups out. Theorist Judith Butler recently pointed out that these laws are evidence that “Parents and communities want to exercise forms of censorship to stop their children from knowing about how the world is being organized and how different people are living their lives.”

This kind of censorship ignores the fact that change is, in many ways, inevitable. The historian Julio Capó Jr. suggested recently that Anita Bryant’s efforts in the ‘70s, though successful in the short term, accidentally inspired a movement. “It got people to see themselves as a voting bloc. It got them to see that their very existence and their rights were very much under attack in a different way than we had seen in the decade prior.” Those people kept fighting for their rights, and in the coming decades they largely succeeded.

Though the language around the anti-LGBTQ+ laws of today and those of the 1970s is in many ways similar, i’s important to note that the target has shifted toward the perceived threat of rights for trans people as opposed to gay people. Already, groups are mobilizing to fight for equality in the face of these new laws and to help the people who are impacted by them, much like they did in the past. It’s a cliche to say that history repeats itself; it’s also true.

Seth Landman

Seth Landman