Founded on April 22, 1996, the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) was first conceptualized as a counterpart to the men’s National Basketball Association (NBA). Ahead of its inaugural season in 1997, the WNBA centered its marketing campaign around the phrase “We Got Next.”

The slogan had a literal meaning; that inaugural picked up just after the NBA’s season wrapped, but it also indicated something more. “It’s the three-word ticket to play in street-corner basketball,” Alison Roberts wrote in The Sacramento Bee over two decades ago. “At long last, it’s now the women’s turn to say it — and to play it.”

Over 25 years later, the WNBA has carved out its own reputation as a premier professional sports league replete with scores of talented players, from greats of the past, like Rebecca Lobo, Lisa Leslie and Sheryl Swoopes, to some of today’s most decorated athletes, like Candace Parker, A’ja Wilson, Breanna Stewart and Sue Bird.

One of league’s more recent mottos, “Watch Me Work,” is a notion that extends beyond the boundaries of a basketball court and into the realm of the league-wide social justice initiatives that have defined activism in sports over the last decade.

To mark the start of the 2022 WNBA season, we’re taking a look back at the WNBA’s origins and the ways in which the league is at the forefront of uplifting players and supporting athletes’ activism.

How College Basketball Ramped Up Enthusiasm for the WNBA’s Creation

When you think of college basketball, there’s a good chance the University of Connecticut (UConn) comes to mind. And, most likely, you’re thinking of the women of UConn, who, alongside long-time coach Geno Auriemma, have consistently pushed the game to new heights. But there was a time when the dynasty wasn’t known for breaking records or shaping some of the greatest basketball players of all time. UConn’s now-iconic legacy really began in 1995.

Just over 25 years ago, the Huskies had an all-star team led by greats like Jamelle Elliott, Jennifer Rizzotti, Kara Wolters, Nykesha Sales and, of course, Rebecca Lobo. During regular season play, the ’94-95 Huskies dethroned the seemingly insurmountable (and then-No. 1) Tennessee, which helped the team clinch an undefeated season.

The first 35–0 season record in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) history is reason enough to celebrate, right? Well, UConn did one better when March Madness rolled around by winning their first national title. And, to do so, they once again defeated Tennessee.

While UConn’s win was monumental for the program, the reverberations extended far beyond Storrs, Connecticut. “Two years after the title, Lobo became a pillar of the newly created WNBA,” Alexa Philippou wrote in the Hartford Courant, “a league whose very existence owed in part to how the ’95 Huskies inspired the country to embrace women’s basketball in a way it hadn’t before.”

The 1996 Olympic Games: How the Women’s National Team Changed Everything

Togethxr, a new, women-led media venture founded by Chloe Kim, Sue Bird, Simone Manuel and Alex Morgan, is producing a six-part documentary podcast series, called Summer of Gold, about this very Olympics. Bird, one of the pod’s hosts, has even credited the ’96 Games with, among other things, launching the WNBA. So, while UConn’s nationally televised then-underdog victory was momentous, it wasn’t the only piece of the puzzle.

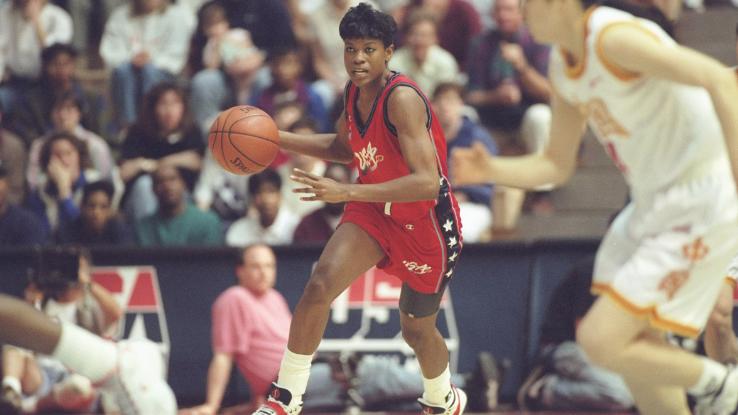

As longtime fans will recall, the 1995-96 Women’s National Team had a real watershed moment at the ’96 Olympics Games in Atlanta, Georgia. Even U.S.A. Basketball is quick to point out that “[the national team] had seen its dominance in the international game wane,” and, undoubtedly, there would be no better time for the team to reassert themselves than on the “home court” of a world stage.

Implementing a more rigorous training program than ever before was a must. Not just because U.S.A. Basketball wanted to clinch the gold medal, but because the association had “adopted a secondary goal of elevating the popularity and visibility of women’s basketball throughout the U.S.”

To prep its Olympic squad, U.S.A. Basketball mapped out a 52-game schedule: The soon-to-be Olympians would face off against top NCAA programs as well as international teams. This landmark training regimen also gave fans the chance to see pro basketballers in action. For instance, the team’s game against UConn drew a crowd of 8,241 attendees — an impressive stat considering that it was just an exhibition game.

By the time the Olympics rolled around, the gold-medal momentum was there. “It was a school-girl level of excitement,” U.S. National Team Director Carol Callan recalled in a 2016 interview with ESPN. “People were screaming on the bus. They’d been playing and training together for a year, and it was time to see the end result.” In fact, the ’95-96 National Team ended their run with an impressive 60-0 record — 52 pre-Olympic wins and eight victories at the games, all of which amounted to the team earning the gold.

“There’s never been a more dominant team in the Olympics in any sport than the U.S. women’s national team,” UConn’s Auriemma, who has since coached several gold-medal national teams at the Olympics, told ESPN. Without a doubt, the team’s victory in Atlanta launched the careers of several now-legendary players — Leslie, Lobo and Swoopes — but it also changed the entire landscape of women’s basketball, creating enough momentum to spawn two pro leagues, one of which had the NBA’s backing.

The Early Days of the WNBA

When the WNBA was announced, another professional league, the American Basketball League, also cropped up. Unfortunately, that league, which began play a year before the WNBA in 1996, would shutter during the ’98-99 season, but the fact that women’s basketball had enough momentum behind it to sprout two leagues remains impressive. Back in ’97, the WNBA was comprised of eight teams:

- Charlotte Sting

- Cleveland Rockers

- Houston Comets

- New York Liberty

- Los Angeles Sparks

- Phoenix Mercury

- Sacramento Monarchs

- Utah Starzz

And, with the full backing of the NBA, it managed to clinch a number of well-known players, including Leslie, Lobo and Swoopes — the first women’s basketball player to get her own signature shoe. On June 21, 1997, the league held its first game, which saw the New York Liberty taking on the Los Angeles Sparks in LA.

In those early years, the Houston Comets dominated the league, winning championship titles in 1997, 1998, 1999 and 2000. The Comets’ breakout star wasn’t necessarily Swoopes, but Cynthia Cooper-Dyke, who ended up being named the WNBA Finals MVP in all four of those winning seasons.

The WNBA Today: Proving That Visibility Matters

Over the years, some teams have moved or disbanded, but, overall, the WNBA has expanded. Currently, the league’s 12 teams are:

- Atlanta Dream

- Chicago Sky

- Connecticut Sun

- Indiana Fever

- New York Liberty

- Washington Mystics

- Dallas Wings

- Las Vegas Aces

- Los Angeles Sparks

- Minnesota Lynx

- Phoenix Mercury

- Seattle Storm

Of these teams, two are tied for the most championship titles: Both the Minnesota Lynx and defending champs Seattle Storm have won four. But the league has always been about more than on-court victories, perhaps because professional athletes playing in leagues like the WNBA have always had to continually “prove” themselves.

For one, there’s the issue of accessibility — that is, game broadcasts aren’t as easy to come by as, say, NBA broadcasts. Fans might tune into ESPN, Twitch or CBS, or sign up for the WNBA’s League Pass to hunt down games. In “(In)visibility,” a 2016 essay for The Players’ Tribune, former Lynx star Maya Moore discusses her frustration with the disconnect. “We need the marketing to match our product,” Moore wrote. “Celebrate us for the things that matter — the stories, the basketball, the character, the fiery competitiveness, our professionalism.”

Not to mention, Moore should be as much a household name as Michael Jordan. Sports Illustrated has dubbed her the “Greatest Winner in [the] History of Women’s Basketball” — and for good reason. Back when she played for UConn, Moore nabbed two NCAA titles and finished her college career with a staggering 150 wins and just four losses.

That winning record continued in the WNBA, where she became a four-time champion and bonafide star of the Minnesota Lynx. “Visibility is nuanced and it can take many forms, from organized youth leagues all the way up to marketing and sponsorships on the professional level,” Moore noted in her essay. “If we want to grow the women’s game, we’ve got to grow the visibility.”

Moreover, there’s the issue of equal pay, which, in a sort of cyclical fashion, relates to the marketing and visibility issues Moore wrote about. With Seattle’s 2020 victory, Sue Bird became the third person in WNBA or NBA history to win titles in three different decades. In fact, both she and NBA star LeBron James have four championship titles under their belts — but that wouldn’t be clear if you looked at their pay. As NBCSports notes, “Fact is, the average WNBA salary, slightly less than $100,000, is roughly 1.5 percent of the average NBA salary, which exceeds $7 million.”

How the WNBA Centers Activism & Uplifts Players

From Tommie Smith and John Carlos to Colin Kaepernick, athletes have always used their platforms and voices to bring visibility to causes and issues that exist beyond the boundaries of a field, court or ring. But, over the last decade, the WNBA has taken athlete activism to the next level. What sets the WNBA apart? It’s not just players who are using the platforms, but a concerted effort from all 12 teams.

The WNBA became the first American pro sports league to openly market to LGBTQ+ fans, hosting Pride nights back in 2014. What was initially framed as rainbow capitalism has since evolved into something more inclusive and genuine, thanks in large part to openly queer, trans and nonbinary players (and their allies) who are consistently using their platforms to promote change and amplify their own visibility.

In 2017, WNBA players Brittney Griner and Layshia Clarendon published an op-ed that opposed Texas Senate Bill 3 (SB3), which aimed to regulate bathroom access based upon one’s “biological sex” and block local anti-discrimination bills that protect trans folks’ rights to use the bathroom that matches their gender. Griner and Clarendon praised activist-athletes who paved the way for them, writing, “As beneficiaries of such brave efforts, we do not take our responsibility as activists lightly. We believe it is our moral duty to use the platform we have been given to speak out.”

By 2018, the WNBA’s Take a Seat, Take a Stand helped raise funds for GLSEN, an “education organization working to end discrimination, harassment, and bullying based on sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression and to prompt LGBT cultural inclusion and awareness in K–12 schools” through Pride Night ticket sales.

And the league is centering its queer players in a way other pro sports leagues simply aren’t. From celebrating Sue Bird’s engagement to soccer star Megan Rapinoe to uplifting Clarendon when he shared they’re trans and nonbinary and underwent gender-affirming top surgery, the WNBA has helped foster visibility. In turn, this allows us fans to see ourselves in the players we love.

“We are so proud that Layshia is part of the WNBA and we know that their voice and continued advocacy will not only support and help honor and uplift many other nonbinary and trans people,” WNBA commissioner Cathy Engelbert wrote in an Instagram story, “but also encourage empathy and understanding for the community across all levels of sport.”

In a recent Sports Illustrated story, “Living Nonbinary in a Binary Sports World,” Clarendon reiterated the connection between sports, belonging and visibility, saying, “That feeling of belonging is invaluable as a young person. I loved the competitiveness of sports, chasing a goal, the camaraderie of being around teammates and how when I made a pass to someone and they scored it felt like we could accomplish anything.”

The WNBA Protests Police Brutality & Racial Inequality

In September of 2016, the Indiana Fever WNBA team joined other athletes — inspired by Colin Kaepernick — to kneel during the national anthem to protest ongoing police brutality against Black folks in America. But this protest was unique. The players took action just before a WNBA playoff game — a high-stakes event with higher viewership — and every single member of the Fever knelt, arms linked. This marked the first time an entire team in any pro sport protested during the anthem.

Just last year, the WNBA showed solidarity again with Black Lives Matter and Black folks in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. As protesters across the country fight against police brutality, the WNBA, and its teams and players, have added to the conversation. “The time for change is now. Enough is enough,” the WNBA tweeted on May 29, 2020, along with a photo of empowerment that reads “Bigger Than Ball.” But that wasn’t where the solidarity ended.

With health risks and players’ financial security accounted for during pandemic shutdowns thanks to the WNBA “bubble,” the league could resume play over the summer — and remain at the forefront of change, especially when it comes to demanding racial justice. Nneka Ogwumike, forward for the Los Angeles Sparks and president of the Women’s National Basketball Players Association (WNBPA), told The New York Times that the season could act as a platform for spotlighting activism, saying, “We’ve always been the first in line to speak about social issues, and we see this as a really magical moment for us to turn the unexpected into something that could be very beautiful, with 144 voices in the same place.”

In July, WNBA players dedicated their season to Breonna Taylor and the Say Her Name campaign, which aims to bring awareness to Black women who are victims of police violence. In addition to wearing Taylor’s name on their jerseys for the duration of the season, players took some of the most radical actions in the pro sports world: Instead of kneeling for the national anthem, teams left the court for the duration of the song.

According to NPR, about 70% of the players in the WNBA are Black, and it’s clear that the league was ready to stand behind their players — and fans — and leverage the sport’s immense platform for good. For years, the WNBA has been leagues ahead of other professional sports leagues when it comes to pursuing societal change and justice, and 2020 cemented the league’s and players’ places in history.

As the 2022 season starts, the league is focused on Brittney Griner, the gold medalist and seven-time WNBA All-Star who’s been detained in Russia since mid-February. Accused of carrying cannabis oil in her luggage, Griner could face up to 10 years in prison. Ogwumike, of the WNBPA, has noted that Griner’s situation stems from pay inequity, saying, “We go over there to supplement our incomes and quite frankly to maintain our game. Our teams encourage us to keep up with our game by going over there and being more competitive. There’s so much that’s at play that, you know, we live politically intrinsically.”

While the league is working with the federal government and other resources to help get the Phoenix Mercury star home, WNBA commissioner Cathy Englebert shared some news ahead of the WNBA Draft. “BG founded an organization in 2016 called BG’s Heart and Sole Shoe Drive,” she said. “The activations that we will do, the Mercury and the league, are intended to remind us of BG’s spirit of giving and do the work she’d be doing if she were here, and certainly the work she will join us in when she returns.”

The 2022 WNBA season starts Friday, May 6, with the regular season running for a record 36 games per team through mid-August. While a dozen live games will be streamed on Twitter — a continuation of a long-standing partnership between the W and the social media platform — this season also coincides with a redesign of the WNBA League Pass. Offering more than 130 live games and every game on demand, the WNBA League Pass is the best place to catch all of the 2022 regular season action.